Part 1: The Will to Remember - A brief over view of the Federal Connection and how it was received; Government denials and Hooker’s liability; how the past disappears from collective memory.

They began working together in 1979 while Hinchey was a member of the New York State Assembly. Hinchey conducted hearings, with full subpoena power, into a wide range of environmental crimes, while Smitty did behind the scenes investigations. In 1992, Hinchey was elected to Congress where he served until 2013. Smitty stayed with him the whole time.

In the early 1980s, Assemblyman Hinchey began investigating the mob’s role in the garbage business, and in 1986 he filed the report, Organized Crime’s Involvement in the Waste Hauling Industry, complete with a chart showing which Mafia family controlled which carting companies. In 1991, Hinchey followed up with another report on organized crime in the Hudson Valley, this one titled, Illegal Dumping in New York State: Who’s enforcing the law?

Well before any of that, the young Assemblyman Hinchey took part in a special investigation into a small landfill near Niagara Falls that came to be known throughout the world as Love Canal. The report his task force produced after a year and a half of research was titled, The Federal Connection.

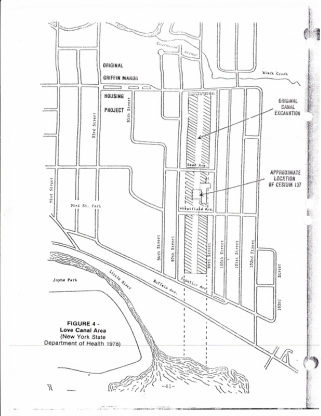

Love Canal burst on the scene, both literally and figuratively, in 1978. Neighbors of the abandoned waste dump began noticing exploding rocks, blue goo, and rotting 55 gallon drums rising to the surface in places not too far from their homes. Michael Brown, a reporter for the local Niagara Gazette wrote a series of stories about the region’s toxic problems that sparked concern and fear among the residents as they learned more about Niagara Falls’ toxic history.

Almost immediately, the New York State Department of Health conducted a study and confirmed that a health hazard existed in the Love Canal neighborhood. The Health Commissioner condemned and closed the elementary school across the street from the old dump. A neighborhood citizens group formed, headed by an anxious young Love Canal mother named Lois Gibbs.

The residents demanded that the government take some kind of action to protect them from the toxic chemical waste that was being uncovered in the old canal. Facing a wave of public pressure, President Jimmy Carter ordered that the homes closest to the contamination be evacuated and the residents relocated. The drama grabbed America and the world’s attention.

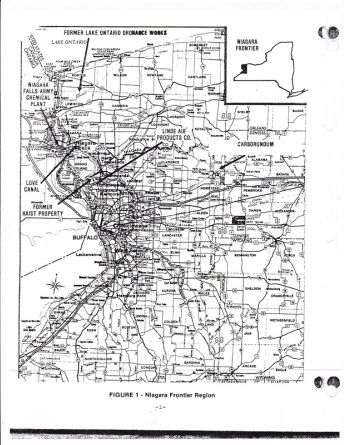

Images from the Federal Connection. Click to enlarge.

Images from the Federal Connection. Click to enlarge. Because this drama was unfolding on their own turf, New York State Government officials wanted to be on top of it. Stanley Fink was the Democratic progressive speaker of the New York State Assembly. He and others in Albany were doubtful when the U.S. Army declared in 1978 that the U.S. Government had had nothing to do with the poisoning of Love Canal. Fink knew that many of the chemical plants in the Niagara Falls region, including Hooker Chemical, had been involved in the Manhattan Project, and had worked closely with the U.S. Government.

Speaker Fink assigned a couple of his aspiring Democratic mavericks to the Task Force that would investigate what happened at Love Canal. One was, of course, Maurice Hinchey. The other was Alexander “Pete” Grannis, an assemblyman representing the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Years later, in 2007, Grannis would be appointed Commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation by Governor Eliot Spitzer. Three years later he would be fired by Governor David Paterson because of a statement he had made in reaction to severe DEC budget cuts proposed by the governor. Grannis had said that the cuts would make it impossible for his agency to enforce the law and protect the environment, especially if New York were to permit hydraulic fracking. Apparently, he was speaking too much truth and was told to resign.

Defense Department officials speaking after their own 1978 investigation had declared, “We’ve taken a look at everything we can and we’ve been unable to verify even a hint of evidence that there was Army dumping at that site.” Hinchey and Grannis, on the other hand, found plenty of evidence to implicate the Army in the contamination of Love Canal, including substantial eye-witness testimony about men who wore Army uniforms and respirators, and who dumped barrels of chemicals out of the backs of Army vehicles. They also found a pattern of deception in the Army’s handling of the investigation. As they saw it, “The ultimate effect of the Army’s investigation and report was to quell public suspicion and whether intended or not, to dampen further investigative efforts.”

Despite the opposition, the Task Force continued their investigation, going through many of the same witnesses and testimony that had been available to the Army, and then taking the research further. The Task Force conducted interviews, obtained corporate and government documents, inspected factories. Smitty used some of the contacts he had made in the American State Department and the British Foreign Office and the War Offices of both countries during the Second World War to track down information about the Manhattan Project.

What the Task Force found is neatly summarized in the full title of their report: The Federal Connection: A History of U.S. Military Involvement in the Toxic Contamination of Love Canal and the Niagara Falls Region.

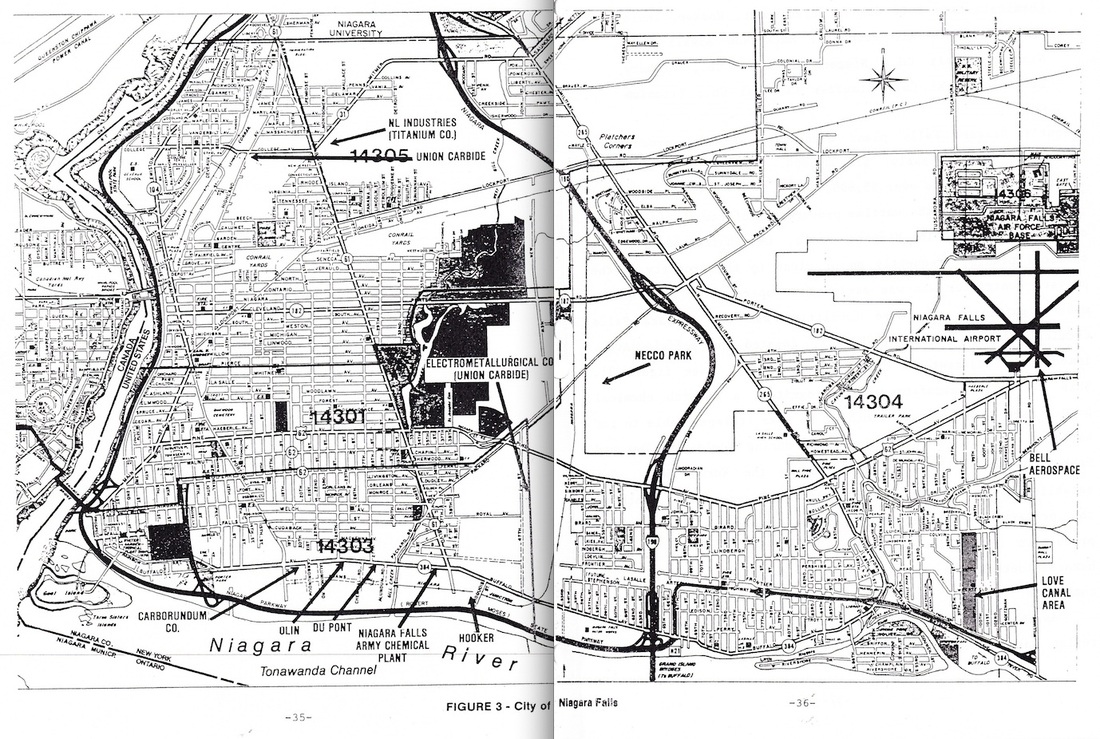

The Manhattan Project designed and built the bombs that were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan at the close of World War II. Raw, super high grade uranium ore mined in the Katanga Province of the Belgian Congo was transported into the Niagara region by way of Canada, and then refined, through a series of elaborate steps that integrated the combined efforts of several different factories and processes, into the fissionable material that was required to make the bombs explode. The big Niagara Falls chemical companies working with the U.S. Government in the early 1940s profoundly altered the course of history by producing the world’s first atomic weapons.

Many of the industrial buildings up and down Buffalo Avenue and the surrounding neighborhoods were engaged in no other activity than the refinement of fissionable material for the atomic bomb. In some instances the factory buildings were owned by the company, while in others, the Government owned the building and supervised the operations. There were different kinds of working relationships between the Government and the various contractors, but few of these relationships allowed for much independence from Government oversight and control.

For example, the Manhattan Project paid for and built a secret, guarded factory building called P-45 on Hooker property. It was operated by both Hooker and Army personnel but run by the military. Hooker described itself as an “agent” working for the Chemical Warfare Service of the U.S. Army, not as a private contractor.

As they expanded their search, the members of the Task Force realized that Hooker made up only one small part of a much larger, and more serious, story. In this context, it seemed highly unfair and misleading to portray the Hooker Chemical Company as the sole responsible party for the contamination of Love Canal. As the Task Force explained In the introduction to The Federal Connection.

The original focus of the Task Force inquiry was primarily on the eyewitness allegations of United States Army dumping of toxic wastes into Love Canal, and the sufficiency of the Army’s 1978 investigation into these allegations… The scope of the inquiry expanded radically as it became apparent that Love Canal and federal involvement there was merely the proverbial “tip of the iceberg.”

1. The disposal of toxic chemical wastes from Army and government-related chemical production in the Niagara Falls region contributed significantly to the toxic contamination of Love Canal.

2. The Army’s 1978 investigation and report did not adequately examine the issue of Army involvement at Love Canal.

3. The Army’s “Manhattan Project” disposed of 37 million gallons of radioactively contaminated chemical wastes in underground wells which the federal government has to date neither monitored nor identified in any of its surveys.

4. Civilian workers at various Manhattan Project and Atomic Energy Commission plants in the Niagara frontier region were, due to primitive federal standards and inadequate protection, exposed to excessive levels of radiation.

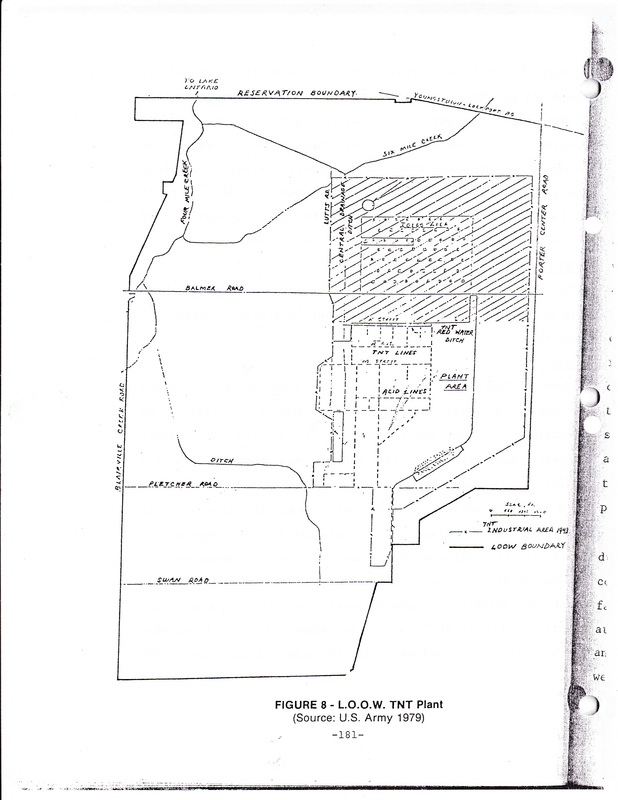

5. The army TNT plant at the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works (LOOW) was never sufficiently decontaminated, leaving an uncharted legacy of TNT wastes and residues in an area now occupied by a chemical waste landfill and treatment facility.

6. The use of part of the ill-suited LOOW site by the Department of Energy and its predecessors has resulted in significant radioactive contamination on and off the federally-owned site.

7. In 1954-1955, the Atomic Energy Commission permitted Carborundum Metals Co. to dump thousands of gallons of untreated thiocyanate wastes directly into the Niagara River through the outfall sewers at the LOOW.

In the course of its investigation, the Task Force discovered that several federal monuments to environmental folly remain in the Niagara and Erie County region - some already a matter of public knowledge and a subject of remedial efforts, and some, shockingly, unknown, and unmonitored. How these sites, born in the crisis of war, were conceived, utilized, and then abandoned is the story of this Report.

The toxic contamination of Love Canal, the transformation of the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works site into a perpetual wasteland, and the dotting of the Niagara Frontier Region landscape with areas of excessive low level radiation are not new revelations. However, the documents obtained by the Task Force and discussed in this Report cast new light and provide a fresh perspective on the origins, operations and potential hazards of the federal enclaves formerly and presently located in the Niagara Frontier Region…

The deleterious impact of the chemical and radioactive contamination left behind by military and government agencies, and the potential health injuries suffered by workers overexposed to radioactive elements at government plants are just now becoming known.

One reason The Federal Connection is not so widely known is because the U.S. Government immediately denied, then distanced itself from the allegations. In May 1980, the Associated Press reported the Assembly Task Force findings that the U.S. military had dumped “radioactive wastes, nerve gas and other highly toxic chemicals at Love Canal and other sites near Niagara Falls.” The Defense Department responded that they had not had time to examine the Assembly report, but a pentagon spokesman added that he "recalled a 1978 department study which found no evidence of chemical dumping by the military in the Love Canal area.”

U.S. Congressman John LaFalce, whose district included the Niagara Falls region, demanded that Congress investigate the “apparent discrepancies between the Pentagon study and the latest Assembly findings.” But the congressional investigation he called for never took place.

In February 1981, The New York Times reported the Assembly Task Force finding that, “The Army and a defense contractor dumped more than 37 million gallons of radioactive caustic wastes from the World War II atomic bomb project in shallow wells at Tonawanda, N.Y,” and that the Task Force had new data to “dispute an earlier denial of involvement in dumping at Love Canal.” A Defense Department Spokesman said the report was “under review,” and stood by the earlier statement that the Army had “no direct involvement” in dumping at Love Canal.

U.S. Senator Daniel Moynihan pledged efforts to get the U.S. Government to investigate the allegations, or, he told the New York State Attorney General, you can “sue us and we might respond.” The federal investigation he pledged never happened, nor did the Attorney General sue the U.S. Government.

The U.S. Justice Department had, in fact, already initiated a $124 million lawsuit several months earlier against Hooker Chemical in connection with chemicals buried at four sites in the city. The court proceedings would drag out into the 1990s, but the U.S. Government’s position was clear and consistent from the very beginning: Hooker did it.

With the passage in 1980 of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), better known as Superfund, a clearly defined federal response to toxic releases had been established, as well as a reserve fund to pay for clean ups when responsible parties could not be found and compelled to bear the costs. Love Canal was Superfund site number one, and Hooker Chemical was going to be the first ever responsible party.

Occidental was not going down without a fight. They counter sued, claiming that the military dumped 4,000 tons of chemical waste into Love Canal, and that Hooker was under contract to the military at the time of the dumping. They argued that the Government was responsible as well, and liable for part of the clean up costs.

In May 1991, Judge Curtin came down hard on the Government’s refusal to cooperate with Occidental’s request for documents. According to Smitty, soon after it had assumed office in 1981, the Reagan administration re-classified many of the documents that he and other members of the Task Force had used while researching The Federal Connection.

Judge Curtin did not like the stone walling, and wrote that "the United States seems to have been guilty of a disturbing naivete when faced with the task of determining whether the Army did, in fact, possess documents pertaining to the allegations.” There was no longer any access to the incriminating information, and without it, Occidental didn’t have a chance of making the U.S. assume responsibility.

Closing arguments were made in February 1992. Thomas H. Truitt, one of the lawyers representing Occidental, argued that the Government had failed to follow up and investigate claims made by residents and employees that the Army had buried waste in Love Canal. He accused the Government of “shameful” and “sordid” behavior and of concealing evidence. He charged that “efforts by the Federal Government to mislead this court and this community have constituted a significant attack on the judicial process…At no time have I seen such a consistent pattern of sham, stonewalling and dissembling the record as this case shows…the gist of the Government's position is that the cover-up worked.”

The assistant U.S. Attorneys on the case argued back that, “There is no basis for claims made by Occidental that the military sanctioned and directed the company's dumping in the 1940's and early 1950’s.”

By this time, Occidental’s reputation was as toxic as the chemicals that were buried in Love Canal. Judge Curtin considered his decision for about two years, finally issuing a ruling in 1994 that Occidental, all by itself, was liable for the clean up of Love Canal. In the same ruling, however, he denied a request by Government lawyers to make Occidental liable for an additional $250 million in punitive damages.

The request for punitive damages seems especially harsh when you consider that Hooker was working for the Government both during and right after the war. Common sense would dictate that the Manhattan Project bore some, if not most, of the responsibility for the contamination of Love Canal. Instead, the Government threw Hooker over the Falls.

The Federal Connection’s disclosures about the Manhattan Project did not seem to have had much influence on the courts as they decided who bore the responsibility for the damages inflicted upon Love Canal and its residents. Occidental ended up paying $129 million as the only responsible party.

Unfortunately, The Federal Connection, with all of its warnings about more buried chemicals and residual radioactivity, exerted just as little influence over the state and federal agencies that over see environmental and health issues, as it had exerted over the courts.

The Federal Connection had been the first to report the dangerous and uncharted conditions at the 7,500 acre Lake Ontario Ordnance Works where TNT had been manufactured and stored on the surface and in a vast network of underground waste lines along with several thousand tons of radioactive residual uranium. The report called on the Government to suspend construction of the new Interim Waste Containment Structure they were building on top of it, and to acknowledge the seriousness of the problem for the first time and to accept responsibility for further testing and any cleanup of the widespread and unaccounted for contamination.

Instead, almost immediately after The Federal Connection was submitted, the Department of Energy began containment and capping work on the LOOW, which by then had been renamed the Niagara Falls Storage Site (NFSS). The new waste containment structure was completed in 1986. Less than ten years later, the National Research Council studied the site and determined that the new chemical landfill was a potential threat to health and the environment and that the cap was destined to fail. Environmental groups to this day insist that the site is leaking radioactivity, but the Army Corps of Engineers assures us that the radioactive waste will be safe there for at least 200 years.

| The Government had hurriedly pushed the waste under a cap at the former LOOW and claimed that the problem had been addressed. They did the exact same thing at Love Canal. In September 1988 The New York State Department of Health concluded that portions of the Love Canal neighborhood were “as habitable as other areas of Niagara Falls.” Given the chemical history of the region, that doesn’t sound like much, but officially it meant that it was okay to live there again. As time passed, perceptions and recollections softened, and people assumed that the clay cap and drainage system that were installed on the landfill were doing their jobs. Soon families began moving back. By 2004 when Love Canal was taken off the Superfund list and declared clean, about 260 houses just north of the canal had already been renovated and sold to new owners. Jane M. Kenny, the regional EPA administrator, remarked at the Superfund de-listing that, “We now have a vibrant area that's been revitalized, people living in a place where they feel happy, and it's once again a nice neighborhood.” |

Removing Love Canal from a federal list should not mean removing it from our historical memory. It should be made a kind of national historic toxic waste site, a reminder of just what can go wrong -- and what can go right -- when corporate, governmental and community interests collide. Love Canal represents one of those moments when ordinary Americans discovered that they would have to fight for their own welfare against corporate interests and against the governmental echo of those interests. The law that established the Superfund is a monument to that moment, and a reminder of a time when the federal government was still willing to side with ordinary citizens.

In an effort to maintain secrecy and avoid liability, the Government pursued a strategy of minimizing the perception of damage, and putting all of the blame on one of its corporate contractors. Hooker was a huge polluting chemical company that was certainly deserving of blame for the mess, but not all of it. The Government was not siding with ordinary citizens so much as it was protecting itself. How necessary has it been, for reasons of national security, to maintain silence?

And despite assurances, Love Canal was still not clean and still not safe, and still not ready to slip quietly into historical memory. The only one who seemed to get it right was Lois Gibbs, the Love Canal activist, who marked the 2004 de-listing ceremony by saying, ''Nothing is different from what it was five years ago except that the E.P.A. needs to look good.”

Not surprisingly, Lois Gibbs returned again to Love Canal nine years after the de-listing to lend support to a recent lawsuit filed by Love Canal residents who are claiming that Hooker’s buried chemicals are still making people sick. ”It was so weird to go back and stand next to someone who was crying and saying the exact same thing I said 35 years ago,” she said.

The new residents, who had been drawn to the neighborhood by promises of cleaned-up land and affordable houses, were experiencing health problems and feeling trapped, just like those of Lois’ generation had. One young couple complained of mysterious rashes, miscarriages, and unexplained cysts since moving into the Love Canal neighborhood. "We knew it was Love Canal, that chemicals were here," the homeowner said, but we had been “swayed by assurances that the waste was contained and the area was safe.”

How could these young families not know? How could they accept the assurances when all of the parties involved in this matter were suspect? Why weren’t they more familiar with some of the information that had been documented in The Federal Connection? If they had, they would have known that a plastic liner and a cap made of clay were not going to eliminate all of the environmental threats in their beleaguered neighborhood.

Why was it that despite everything, some of the fundamentals had not been learned in 35 years? Clearly, the actions of the U.S. Government, across branches, departments, and agencies, were directed toward minimizing discussion about the Manhattan Project as it relates to the pollution of the Niagara Falls region. It is also clear that large American news organizations, like the New York Times, basically stuck to the official Government version.

If you do a Google search for “Manhattan Project Love Canal” you will find information, but not as much as you might hope. Several articles were written this past year on the 35 year legacy of Love Canal, but the Manhattan Project is rarely if ever mentioned in these toxic legacy retrospectives, nor is Love Canal’s connection to the creation of the atom bomb. Undoubtedly, readers would learn a lot by seeing how the Love Canal disaster fits into a larger picture, but there is barely a hint. One of our culture’s most iconic environmental stories is only partially understood.

Our news media have sanitized and diminished the event. Their reporting functions something like the clay and plastic cap that covers Love Canal; it defines and contains the matter from seeping out in scattered directions, and it reassures us that we are safe from harm. Both pacify us and cover-up what is occurring beneath the surface.

It would be a different world if our major news outlets consistently told us stories that aimed deeper for the truth. Sadly, most of the stories would arrive at the same awful conclusions. We would be reminded constantly that we have poisoned our earth. We would read everyday that our governments have neither the will, the integrity, nor the capacity to address our problems, nor are they likely to do so. Maybe we would stop reading.

Fortunately, there are people who are collecting data, maintaining records, and writing stories that go deep into the history of the Niagara’s Manhattan Project plants. For example, there is a wealth of information on the For A Clean Tonawanda Site (F.A.C.T.S.), maintained by a coalition of concerned citizens who stand for the removal of all radioactive waste from local Manhattan Project sites. They have a PDF library that contains a scanned copy of The Federal Connection including the volume 2 appendices.

There are also committed writers like Geoff Kelly and Lou Ricciuti who have been researching the history of the Manhattan Project, picking up current developments, and reporting all of it for the last several years in Artvoice, a Buffalo area culture magazine.

They wrote a story in 2008, for example, about historical amnesia and the large quantities of radioactive material that lie buried under streets that were scheduled for pothole repair. Discovering radioactivity shouldn’t be a surprise in Niagara Falls, given what happened there. Back in the early 1980s the Oak Ridge National Laboratories had identified “more than 100 radioactive hotspots in Niagara Falls, including in its roadways.” But the discovery of radioactive fill in the roadway was a surprise. Typically, according to Kelly and Ricciuti, people had no idea where the radiation might have come from.

Many of the 100 hotspots had never been remediated or investigated and had quickly dropped out of “everyday consciousness.” And most folks had no historical memory of the LOOW and the radioactive wastes that had been sloppily contained there since the war, nor did they understand how careless oversight over the years enabled some of that material to find its way into the fill used under the streets.

One of the people who was puzzled by the discovery of radioactive fill was a Niagara City Councilman. When he was given a copy of the Oak Ridge surveys, he could see for himself the extent of the radioactivity around his city. He acknowledged his community’s hazy historical memory of its chemical and nuclear past. “We know what we were at one time, but I think everybody believes that it was contained to Love Canal.”

All that stands between us and this fatal forgetting are the grassroots activists, journalists, academics, and archivists who locate and preserve the evidence, then contribute to the public awareness. It is hard, but necessary, work, for as all activists know, no one else is going to do it for us. That’s what Lois Gibbs and her neighbors learned 35 years ago, and it is the thing that Ralph Nader urges us to remember most about Love Canal’s legacy: “that collective citizen action is a powerful agent of change.”

He’s right. It is. But if we allow ourselves to forget where the toxic stuff is buried, it will keep re-appearing to haunt our children. Succeeding generations will take their turn, as Lois Gibbs and her neighbors did, and as terrified young couples are doing right now, discovering cysts, rashes, miscarriages, and tumors, all the while wondering why, and not knowing where to go for the answers. Collective citizen action must be accompanied by collective accumulated knowledge, or there will be no real change, just recurring heartbreak.

The first step toward real change is recognizing the real problem. The world’s first atomic bombs were manufactured in the neighborhood of Love Canal. After they were dropped, the U.S. Government did not want the world to see what the two bombs had done to the populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Government didn’t want the world to see what the bombs had done to Niagara Falls, either. But unless we are able to look squarely at what was done, we won’t ever be able to fix it.

In my recent conversations with Smitty I ask him how it feels to know that The Federal Connection has pretty much gone unheeded, nearly erased from public consciousness.

He tells me about the trips he took to the government archives in Virginia from 1979 to ’81; the documents he located that identified what had been dumped and hidden and flushed, how it got there, and where it sat, and still sits. “The Government lawyers and investigators,” he tells me. “They never even bothered to look at this stuff.”

Coming soon - part 2: The Federal Connection

RSS Feed

RSS Feed