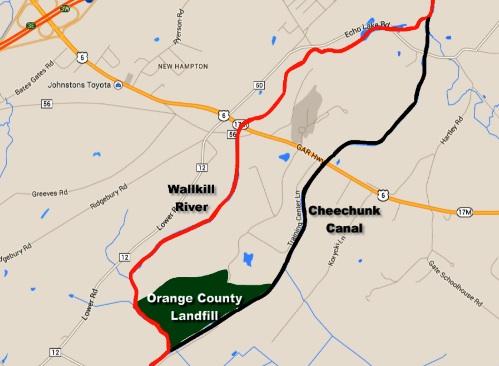

There are no easy solutions. Large, often competing interests are at stake here. Immediately upstream are sixteen thousand acres of black dirt farmland, providing essential food for New York. The farmers are concerned about flooding, and want the canal maintained and kept clear to provide good drainage when the heavy rains come. Downriver communities, on the other hand, rely on shallow aquifers along the Wallkill River for drinking water, and use the river for recreation as well as wastewater and storm water management. They worry that upstream dredging might destabilize the river banks and the landfill, and send more contaminants their way.

This location demands our attention. If we look carefully, the place itself has something to tell us, maybe even the solution to the problem. What can we learn by studying this spot, the junction of Black Dirt, Cheechunk Canal, and Orange County Landfill? Why are all of these things precisely here? By considering the historical and geographical roots of the impasse, we may be able to see the bigger picture and come up with more comprehensive solutions.

The early inhabitants of this region believed that a people had to know their history in order to make good decisions in the present, and that a people must also be ever mindful of the well being of future generations. Here we will try to apply this long vision method to a particular setting and the choices that have already been made there, as well as those that still face us.

Prehistory

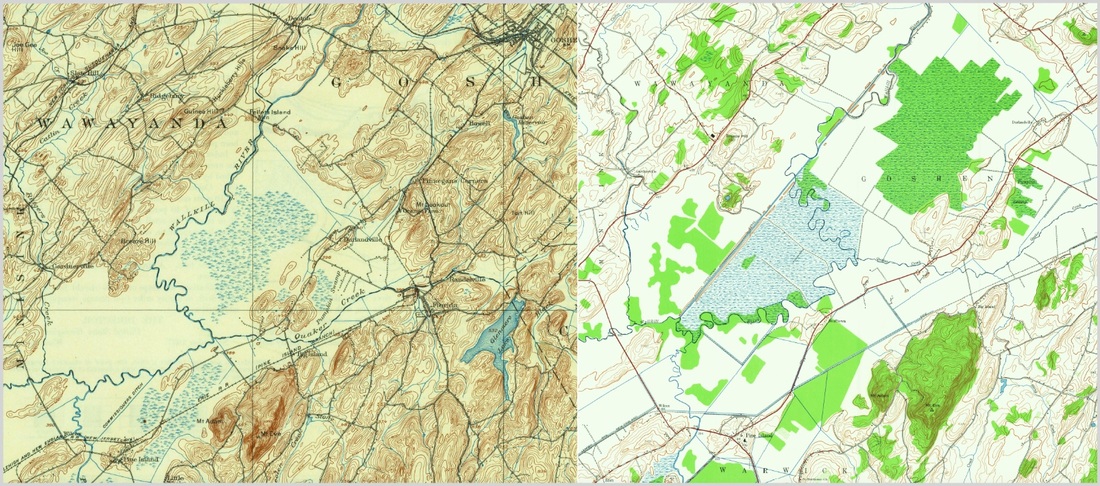

Moraines were left behind by the glaciers, marking the points of the ice’s furthest advance, or the stages of its retreat, like the Pellet’s Island moraine and the New Hampton moraine, both in the immediate vicinity of today’s landfill and canal. The mounds are collections of granite boulders and drift, torn by the glaciers from the Shawangunk Ridge, twenty five miles to the west. The glacial debris that was deposited around present day Denton, New York blocked the northward flow of the melting ice, leading to the formation of a huge glacial lake in this part of the Wallkill valley.

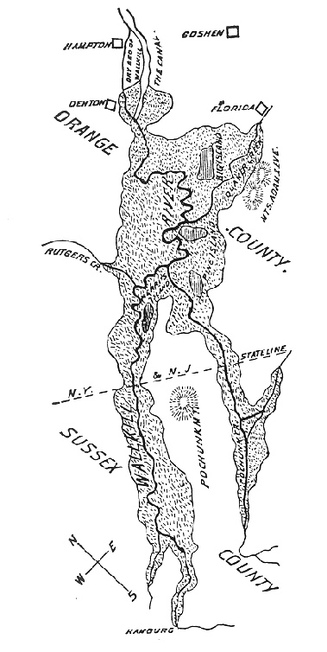

The lake eventually drained further, leaving behind a bog which backed up for twenty miles, from the New Hampton moraine in the north, to present day Hamburg, New Jersey in the south, where the swifter waters of the upper Wallkill poured down from Lake Mohawk. North of Denton and beyond the wall of rock, the current of the Wallkill picked up speed again for the remainder of its course to Rondout Creek, then the Hudson River near Kingston.

In his 1881 History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, Richard Snell referred to the middle stretch of the Wallkill from Hamburg to Denton as “one of the crookedest streams in New York State.” Because there was only an eleven foot drop in elevation, the river meandered back and forth across the wide, flat valley. The bed of the river contained a series of “limestone reefs” which were from five to ten feet high. These rock barriers impeded the flow of the river. But the biggest impediment of all was the wall of glacial rubble at Denton.

In the spring and after heavy rains, the entire valley floor south of Denton was often flooded. Snell described the post glacial environment:

The accumulated waters of the Wallkill were forced back over the low country bordering its course and that of its tributaries, the surplus water pouring over the crest of the wall and continuing then in uninterrupted flow to the Hudson at Kingston. Thirty thousand acres of land in Orange County and ten thousand in Sussex were thus converted into an impenetrable marsh covered with rank vegetation. In time of freshets the entire valley from Denton to Hamburg became a lake from eight to twenty feet deep.

Humans made their way to the same valley before the mastodons disappeared. When the last glacial period began more than 110,000 years ago, homo sapiens were just starting a long, slow period of dispersion from Africa into Europe and Asia. It is not clear exactly when, or how, humans first made their way to the Americas, whether by the Bering Land Bridge or across the Pacific or Atlantic. What we do know is that approximately 12,000 years ago, Paleo-Indians wandered into what is now upstate New York, following the abundant game into the lands newly exposed by the receding ice sheet. The oldest human artifacts found in New York State were buried in caves on Mount Lookout, only a couple of miles southeast of the present day landfill and canal.

Some local archaeologists believe that there was at least one other Paleo-Indian site near the northern end of the Cheechunk Canal, where it rejoins the original channel of the Wallkill. Here they had found spear points and other artifacts belonging to “Ice Age hunter-gatherers.” Unfortunately, efforts to explore the possibility that other Paleo-Indian sites are located at the edge of the former drowned lands have been hampered by existing and encroaching development.

History

Native American culture evolved through several periods after the ancient Paleo-Indian. In the Archaic period from around 8000 BC to 1000 BC, Native Americans continued to live nomadically, but developed new tools and increased their population. In the Transitional and then Woodland periods that lasted until the Europeans arrived, Native Americans settled in communities, built permanent structures, traded extensively, practiced agriculture, and developed a complex cultural life.

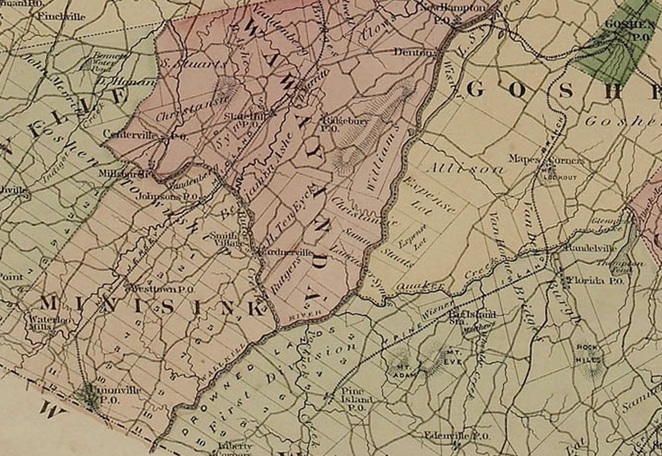

When the Contact period began, the Native Americans who lived in the valley had already organized into part of the vast Lenape Nation which extended all along the Delaware River watershed and into the Lower Hudson Valley and Long Island. At first, the arrival of Europeans did not have much effect on the Lenape along the upper Wallkill, a river that they had long ago named Twischsawkin. As late as 1698, there were only 219 Europeans and Africans living in all of Orange County, far out numbered by the original inhabitants. Even by 1723, the Orange County census showed only 1,244 non native residents. But the slow pace of settlement soon picked up.

We set forward with a guide from Maheckkamack (present day Port Jervis) through the hills, through which we steered along a very blind path over very stony ground till we arrived at a branch of Hudsons River called Wallakill, at an Indian plantation in good fence, and well improved, raise wheat and horses, over which we led our horses by the side of a canoe, it being about 12 perch ( a couple of hundred feet) wide, with a great quantity of water, by the time we got over it was almost dark but we stood for Goshen, being about 3 miles distant… The Indian town aforementioned called Chechong in our path.

As the European settler population grew, the native population diminished. By the time of the American Revolution, less than sixty years after Reading made his visit to Chechong, almost all of the native population of Orange County had either died, been assimilated, or left the region. Many of the Lenape moved west to Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Ontario. Most tellingly, the Lenape and their predecessors left very few marks on the land that they had inhabited for almost 12,000 years. Not unlike the mastodons, the traces that they left behind were fragmentary and buried.

But even though Native Americans left the land the way they had found it, they contributed enormously to our collective knowledge and culture. Part of their contribution is a philosophy of life: a way of being in, and living upon, the earth. The philosophy of the Lenape, just like the Constitution of the Iroquois Nation, promoted respect for the earth and its creatures, as well as a sense of responsibility for generations both past and present. The idea of making decisions that honor the lives and strivings of the dead, as well as provide for the wellbeing of the unborn, is the essence of the Native American concept of the seven generations.

By an interesting coincidence, shortly after the Lenape exodus from the Wallkill Valley, and only a little more than seven generations before our own time, the European settlers made the far-reaching decision to leave their mark and alter the landscape, looking for ways to drain the Drowned Lands and turn the bogs into farms.

When the post glacial lake began receding more than 12,000 years ago, the lake bed filled in with vegetation which decomposed into rich soils. The wide and flat valley floor, the intermittent floods and immersions, and the repeating cycle of growth and decay contributed to a thick layer of muck that in some places reached depths of thirty feet. No surprise, the abundant and rock-free black dirt soon proved to be incredibly fertile, capable of producing bountiful harvests of high quality vegetables like onions, celery, carrots, and beets. The only problem was water.

The first farmers in the Drowned Lands raised cattle among the bogs. It was tricky business that required keeping the cattle up in the high lands, or islands, and out of the swamps. When there were heavy rains, herdsmen had to round the cows up the hills, or the animals would be swept away. Many were lost.

The early settlers of the Drowned Lands had a name for the place that would one day be called Denton: they aptly named it Outlet. Outlet was where the glacial boulders blocked the Wallkill’s way, much the same way that a plug stops up a drain. The very first attempt to pull the plug and drain the bogs was made in 1772 by landowners Henry Wisner and William Wickham. They tried breaking and moving the rocks that made up the biggest ledge impeding the river’s northward flow.

They did not succeed. The ledge, according to Art Soons who farms the land where the ledge still sits, “is made out of some of the hardest rock imaginable. For thousands of years it was compressed by the weight of the glacier. It’s almost impossible to break through it.” But the early farmers kept trying, raising money in 1775 and again in 1803 to pay for the work.

By 1804, the scope of the project had expanded so that the farmers were now digging long narrow ditches to help the river drain more water. In 1807, Drowned Land owners convinced the New York State Assembly to appoint a commission to “raise money by assessment for straightening the Wallkill.” The commission was given the “full power and authority to remove all obstructions out of the bed of the Wallkill at the outlet of the said Drowned Lands and deepen the river to any depth they should deem proper and to widen and straighten the same from any distance above Pellet’s Island bridge.” The “commissioners’ ditches” that can be found up river of Pellet’s Island are a result of efforts that began around two hundred years ago.

But the farmers were not getting the results that they wanted. From 1807 to 1826 they spent approximately $4000, in what, according to local historian Frances Wilcox, “seemed an impossible task.” (The Cheechunk and the Drowned Lands, The Outlet Ditch or Canal Which Changed the Course of the Wallkill, 1925. Excerpt here.) The Commissioners’ ditches were dug for drainage, but they usually filled only with mud. The ditches produced other unexpected results as well. In the fall of 1817, hundreds of thousands of eels, weighing as much as eight pounds each, came down through the channels. George Phillips, a mill owner two miles downriver in Hampton, today’s New Hampton, trapped over two thousand eels in one night, and managed to salt down twenty barrels of them.

Mr. Phillips and the Drowned Land farmers soon learned even more about unintended results, or side effects, that were not part of anyone’s original engineering plans. In the two miles below the rocky ledge at Outlet, the Wallkill River fell twenty four feet, more than twice the fall of the previous twenty miles. A number of Hampton landowners, every bit as industrious as their neighbors in the Drowned Lands, took advantage of the drop in elevation to build a dam and a mill pond, and use the resulting hydro power to operate several mills.

At first, the mill owners of Hampton and the farmers of the Drowned Lands were able to work together. Around 1807, the commissioners could see that their ditching efforts were being thwarted by the dam in Hampton which kept the water level high. The farmers struck a deal with Phillips to pay him to lower the dam at various times of the year so they would escape flooding. According to Mr. Snell’s account, Phillips stopped lowering the dam when the farmers stopped paying him. The river bed ditching was therefore doomed to failure. A bigger step had to be taken.

In April 1826, the State of New York gave the commissioners power to expand their efforts and dig a channel with the intention of diverting the river. This was, after all, the great canal building period of New York’s history. According to Mrs. Wilcox, “The proposed construction of the canal alarmed the people of that part of the valley at Hampton down to Phillipsburgh. It threatened ruin! Two hostile parties arose.” A long and bitter struggle took place between the upstream farmers and the downstream mill owners. In addition to legal arguments, there were fist fights and threats of greater violence, but in the end, the mill owners could not stop the legislature or their neighbors. Work on the ditch finally got started in 1829.

Phillips and the mill owners of Hampton had wanted the excavating work to be done in the bed of the river, not in a new channel. Their livelihoods depended upon the old channel and the mill pond that kept their water wheels turning. The legislature granted Phillips the right to construct a floodgate at the entrance of the new canal so that the new channel could be closed at certain times of the year to keep the millpond at Hampton filled with water.

George Phillips’ floodgate at the mouth of the canal was also washed away, and the wider, deeper, swifter canal captured almost all the water from the old channel, from the inlet to the outlet. In desperation, Phillips took matters into his own hands. Wilcox wrote:

He built a solid dam at Cheechunk across the canal. He had no authority to do it, but he did it, and the dam turned the waters back in the river’s natural channel and the factories at Hampton resumed their work for a time. But the water was forced back on the low lying meadows, and these fertile acres were again flooded. Then a body of Drowned Land farmers marched down on this Cheechunk dam and demolished it.

The courts ultimately ruled in 1871 that no more dams were to be constructed. The Muskrats had won. Years later in 1900, there was a lone legal attempt to reopen the old channel and close the canal, but that proposal went nowhere. The canal prevailed, as did the farmers’ efforts to drain their land. Snell wrote in 1881:

More than ten thousand acres of swamp were converted into the most productive land in the county. As the canal deepened and widened the drainage of the swamp enlarged in extent. Where, a few years before, the farmers could get about only in boats, solid roads were made possible. Fragrant meadows took the place of almost unfathomable mire. The increase in the value of the property thus drained is today put down at over two millions of dollars. The draining cost the landowners sixty thousand dollars.

What brought wealth to the Drowned Lands farmers, however, sent disease and ruin to the mill people… The Wallkill, from the head of the canal to New Hampton, was changed from a rapid stretch of stream, three miles in length, to a series of stagnant pools and beds of decaying vegetable matter. Denton and New Hampton, situated in the very midst of Orange County's fragrant meadows and mountain air, became seats of malaria. The mills and factories were closed.

But “disease and ruin” were not the only aftereffects of the Cheechunk Canal. Cheechunk Springs were located near the Wallkill River, three miles from Goshen, and just below the mills of Hampton. The spring water used to gush out of the ground warm and clean, and was reputed to have healing powers. In all likelihood, the springs were another of the more significant reasons why unnumbered generations of Native Americans had remained in this neighborhood.

“Cheechunk,” Mrs. Wilcox wrote in 1925, “is an Indian name, and one hundred years ago, these springs were considered medicinal, being both iron and sulfurous. People came by ox-teams many miles to obtain this water.” The American Mineralogical Journal of 1810 mentioned the springs, and its already established celebrity with those seeking cures. Cheechunk Springs and the baths, inns, and guest houses that grew along side them were as popular as Saratoga.

The culture that grew up around the springs was described in the Warwick Valley memoirs of Eliza Benedict Hornby. Under Old Rooftrees was published in 1908 when Mrs. Hornby was eighty years old. She had been born back in the time when work on the canal had just begun. In one of her reminiscences, she wrote about country doctors, and the cures that could be had at Cheechunk Springs.

Baths were kept for visitors. They were advertised as a delightful retreat for the invalid, and a pleasure-ground for those in pursuit of recreation. Daily stages ran from Newburgh to Goshen, and from thence to the springs. The farmhouses in the neighborhood blossomed out into boarding-houses for the visitors. Jolly parties of the country belles and beaux, “on pleasure bent,” rode over to Cheechunk and danced and had a general good time… The Cheechunk House was a scene of life, light and gaiety for years… Those acquainted with it ever recalled its charms with vivid delight, and children loved to listen to their elders' tales of Cheechunk.

After the Cheechunk Canal was completed, the pace of change in the upper Wallkill Valley accelerated. On the positive side, the canal did what it was designed to do. Thousands of acres of cedar swamp and bogs were converted into highly productive farm land. More ditches and drains were dug, and more rich organic soil became accessible. The canal was respected and properly maintained. Nutritious food was produced in abundance in close proximity to the largest market in America. A growing number of farm families were able to support themselves and the local economy through their hard efforts on the superabundant new soil.

In the 1850s, many Irish families emigrated to the valley and grew potatoes in the black dirt. They were followed in the late 1880's by Polish families who accompanied Father Nowak to the tract known as “The Mission Lands” to establish their farms. Their labors converted more swampland into the cultivated fields that have come to be regarded as the richest in Orange County. At the same time, a vibrant farm culture grew up in the valley, steeped in tradition, knowledgable and proud.

Despite the success of the farms and the widespread bounty and prosperity that were evident in the valley, Mrs. Wilcox, the author of the narrative The Cheechunk and the Drowned Lands, expressed misgivings about the canal. Writing in 1925, approximately mid-way between our own time and the time when the canal was built, she worried that the project may have been a mistake. She wrote of “the destructive existence of the canal,” which had taken on a life of its own, and warned that it was going to be up to succeeding generations to keep watch over the channel, and manage it, or the canal would create even greater problems in the future. It now appears that her warnings were eerily prescient. We have not been paying attention to the canal, and the problems are indeed getting away from us.

She proceeded to speculate about alternate histories, wondering what would have happened if things had not been done the same way. What if the canal had not been built, she asked, and the problem of flooding had been confronted differently?

The purpose of the canal was to relieve the Drowned Lands during the spring and fall floods. Had the same energy and means been used toward digging out the rocky bars in the Wallkill, thus allowing the water to flow freely down the main channel, it would have been better for all concerned. Middletown would then have been a deserted hamlet, not a city using the Wallkill River for sewage disposal.

The pace of change has made it harder for us to isolate specific decisions and analyze their consequences. Unlike Lenape culture, Western culture has wholeheartedly embraced the idea of improvability and progress. Our culture has faith in technology, and we enthusiastically and unquestioningly accept each innovation with open arms, unmindful of repercussions. The Native American inhabitants of the valley were better able to apply the principle of seven generations because they were not on as rapid a trajectory of change as their new European neighbors. Native Americans were able to enjoy more continuity through the generations. Our culture accepts the idea that our grandchildren’s lives will be very different from our own, just as our lives differ from our grandparents’. Perhaps we allow our uncertainty about the future to serve as an excuse for not considering the spin-off of our actions more carefully.

Just as the black dirt farmers of the early 19th century could not predict the future consequences of their actions, neither could the farmers of Mrs. Wilcox’s generation predict the outcome of the significant decisions they would soon be making. In 1925 most farming was done with horses on small family farms. There were very few tractors. The coming “green revolution” had not yet changed the face of agriculture. But soon the introduction of fossil fuels into agricultural production would be as strong a catalyst for change as the canal had been.

In 1925 according to the agricultural census, there were 3,706 farms in all of Orange County. By 2012 that number had dropped to only 658. While the total number of farming acres in the county went down from more than 533,000 in 1925 to 88,000 in 2012, the average size of an individual farm almost doubled, as did the number of large farms with more than 500 acres. In 2012, Orange County farmers had almost $77 million invested in machinery and equipment. Back in 1925, the cost of farm machinery wasn’t even tallied up for the census.

As we have already seen with the lesson of the muskrats and beavers, almost every large scale human endeavor that brings success also brings with it unintended aftereffects. No longer dependent solely on the energy of the sun, farmers now relied on petroleum based energy, pesticides, and fertilizers, and were thus able to produce much higher yields. They also incurred much greater expenses.

Economic pressure brought about by the green revolution has been especially hard on black dirt farmers because their land is profitable for farming, but suited for little more. One can not build on top of muck lands, not even an international jetport, as the New York Port Authority ultimately determined in the early 1960s. Once the drowned lands became the farmed lands, there was nothing else to be done with it except plant crops. Unfortunately, black dirt farming in the valley increasingly meant competing in a volatile and high risk market with little room for error and the constant threat of floods. A black dirt farmer in 1990 claimed that fifteen or twenty years earlier, it had cost about three hundred dollars to produce an acre of onions which paid him five or six dollars for one hundred pounds. “Today, it's fourteen hundred dollars to produce an acre of onions, and last fall we only got seven or eight dollars.” The green revolution created more stress for the farmer.

American farming in general, and black dirt farming in particular, also generated what American farmer and essayist Wendell Berry called, “externalized costs.” These are aftereffects like pollution, soil erosion, land destruction, and more recently, shrinking bio-diversity. Berry wrote that these aftereffects are the result of “short term economics,” or what he called, “the economics of self-interest and greed,” because the externalized costs are usually passed on to others. “People who are concerned about what their grandchildren will have to eat, drink, and breathe tend to be interested in long-term economics.” Long term economics, he went on, are like “the golden rule across generations.”

Ultimately, because of its dependence on fossil fuels, much of the agriculture practiced in the world today is necessarily based on short term economics and is not always in the best interests of all. Desperate financial considerations all too often lead to poor choices. Here as everywhere else, farmers in the black dirt region sometimes employed methods that either intentionally or unintentionally abused the land and soil, fouled the air and water, or exploited farm labor.

Shortly after World War II, western farmers as well as home gardeners adopted the use of petroleum based pesticides like DDT, nitrogen based fertilizers, and genetically altered products before fully understanding what kinds of deleterious side effects they might have. As we have become more aware of the dangers, we have turned to more environmentally friendly alternatives, but in many cases considerable damage had already been done.

In 1997, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation conducted a study of the Hudson River’s tributaries, and found that the Wallkill had ten times the concentration of DDT of any of the major and minor tributaries tested, and the highest concentrations of the insecticide dieldrin. The report was able to pinpoint the source of the pollutants as the black dirt region, while noting that the contamination had spread down the whole length of the river, possibly even into the Hudson and New York Harbor.

We can ask the same kind of question that Mrs. Wilcox asked. Would the river now be cleaner If the canal had not been built? It is not difficult to establish a causal link between the construction of the Cheechunk Canal in the 1830s and the DDT contamination of the Wallkill River today, but there are countless other decisions, large and small, that contributed to the DDT pollution as well. Even when big projects are well intentioned, they can lead to big, unexpected changes. If nothing else, looking back seven generations teaches us how difficult it is to make a significant decision affecting many lives and entire ecosystems, with the complete confidence that you will do no harm. Momentous decision making requires a mindfulness which is rarely employed when we rush to build.

The landfill

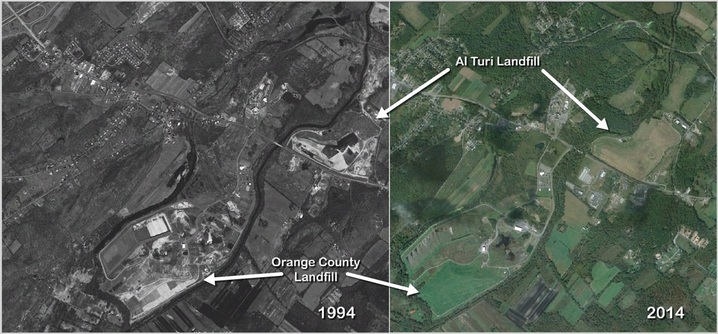

In 1974, the government of Orange County, with the approval of the government of New York State, created the seventy five acre landfill within a larger parcel of land, and began accepting municipal garbage at the site immediately. The landfill was bordered on three sides by the Wallkill River and the Cheechunk Canal, right near the point where George Phillips had built his floodgate at the inlet of the canal about one hundred and forty years earlier. It was constructed without a liner, the mistaken assumption being that the fine clay and silt beneath the garbage mass would prevent liquid waste from leaking down into the largest fresh water aquifer in Orange County.

The County had argued that it had a pressing need to find a place to bury its garbage. Until that time a number of smaller municipal landfills dotted Orange County. The new county landfill was seen as a way of consolidating services. From 1974 until the landfill closed in 1992, seven million tons of garbage were carted in from all over the county and deposited at the landfill. Unfortunately, out of county garbage also found its way in, filling the landfill to capacity well before its time.

Why would anyone build a landfill near a place that was once named Outlet? Here is located the drain for the upper Wallkill River and the rain waters that fall on the majority of Orange County’s black dirt farm lands. Here also is a wetland serving as a window into a huge aquifer and potential source of fresh water. Incredibly, it was common in New York State, in the middle of the twentieth century, to site landfills on top of aquifers. Several of Orange County’s smaller landfills are sited on top of aquifers as well. It was not until August of 1985 that the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation issued an order prohibiting the building or expanding of any more landfills on top of aquifers. The big question is why it took them so long.

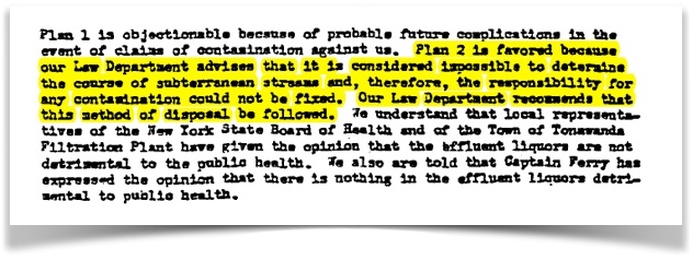

Low lying wetlands near rivers and streams were often used for landfills because the land could not be developed for anything else. Economic as opposed to environmental considerations drove the decision making on where to site landfills, incinerators, and other undesirable and highly polluting projects. Despite everything the human race had ever learned about taking care not to foul the water downstream because someone might be drinking it, that is exactly what we did.

In a 1992 interview, Orange County’s first county executive Louis Mills stated that the decision to site the landfill on an aquifer was made by “Rockefeller’s men” in the recently created Department of Environmental Conservation. By 1995, “Pataki’s men” in the DEC shut the landfill down, refusing to consider the county’s bid to expand the landfill in violation of the State’s new guidelines to protect drinking water.

The second county executive, Louis Heimbach, who was in office for most of the landfill’s life, insisted that the landfill was designed and built with “the best scientific evidence we could muster.” But everything about the landfill’s construction, location, and operation fails the seven generation test. Within two years of the landfill’s construction, leachate had already found its way into the adjacent water courses, which should have been no surprise since the aquifer flowed toward the Wallkill. To make matters worse, the landfill was accepting truckloads of waste illegally, in violation of environmental rules that prevented certain types of garbage from going into municipal landfills.

Carting companies controlled by the Mafia dumped industrial toxic waste from all over the New York metro area into the Orange County landfill, as well as illegal red bag waste from local hospitals including the Keller Army Hospital at West Point. Landfill employees and state police received cash and gifts as payoffs from the mobsters who owned the garbage trucks. Tickets that were written by sheriff’s deputies and presented to organized crime haulers disappeared, never making it to court. Toxic and red bag wastes were plowed in along with the rest of the garbage, and landfill leachate was frequently pumped directly into the canal, in violation of state regulations. Politicians, state and local, knew about the problems and kept quiet.

The same year that the landfill opened, another disposal site only a mile and a half down the Cheechunk was purchased by the Al Turi Landfill Inc. The forty three acre site was owned and operated by organized crime figures who ultimately were found in 1999 to be "unsuitable" to run a landfill. The operation of the two neighboring landfills have come to symbolize a period of lawlessness, a time when the police looked the other way and politicians, according to one local sheriff, kept their mouths shut, “because they were corrupt, incompetent, or scared to death.”

Instead of performing good stewardship of the county’s natural resources, the civic leaders who designed, built, and operated the landfill created a time bomb for future generations. They had responded to a pressing need for a garbage facility by ignoring more pressing needs for clean water and an unobstructed channel to drain the black dirt. Building an unlined landfill on top of an aquifer and next to the canal made no sense. This was, after all, the Cheechunk chokepoint. Had they forgotten all of their history? Michael Edelstein, president of Orange Environment, summed it all up when he said two years ago, "You could not have put a landfill in a worse place.”

“The sewage treatment plants and landfills did not come to the river by accident,” said Ann Botshon, coordinator of the Wallkill River Task Force in 2002. “In the late 1960s, influential developers and planners decided the Wallkill would be the sewer of Orange County, the place where bad things should drain.” Peter Garrison, the former Orange County Planning Commissioner, told us the same thing in a 1992 interview, that given all the wonderful things the County could have done with the Wallkill as a resource, they had opted instead to turn the river into a sewer. Responsible stewardship had been superseded by “poisoning for profit.”

The present

With the exception of important work done by the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s, our State and Federal governments have done little to maintain the canal and drainage system, despite its historically vital role in black dirt region flood control. No one seems to be paying attention except the farmers. They are worried, and rightly so. The black dirt region has flooded with a terrifying regularity over the last hundred years, overwhelming the farms and destroying the crops. As National Geographic described the rising Wallkill in 1941, “Floods come up fast, stay long, and recede slowly. If the waters stay too long, the seed and onions rot; if the run-off is too fast, soft dirt, seeds, and onions go with it.”

The farmers also feel abandoned. They believe they have an understanding with the government to maintain the canal because the job is too big for the farmers to undertake themselves. If you want farms, they argue, you have to help us protect them. The farmers want the government to dredge the canal, clear the banks, and open and maintain the feeder channels. They are waiting for any kind of help, even though it’s generally understood that nothing short of a massive engineering project will solve the problem.

Assistant New York State Attorney General Timothy Cohan, who attended the full day hearing along with members of the farmers’ association, stated that the Senate had a duty to continue the project. “If it is nothing else, it is a moral obligation.” The positive response from the Commerce Committee, and the commitment from the State of New York to plan, construct, and maintain the drainage channels were the strongest assurances the farmers ever received. In fact, the State established legally binding requirements to keep the ditches clear.

Nonetheless, the promises were not kept, the obligations not met. The channels were often neglected, and the canal was allowed to become overgrown while its important function was ignored when the landfills were permitted alongside it. After a particularly devastating flood in the spring of 1983, the Army Corps of Engineers came back to the Wallkill Valley and did some brush snagging and clearing along the canal banks. The Corps conducted a study which concluded that additional dredging was necessary along with the possibility of modifying the channel. They promised to return once they had secured the necessary funding. They have not been back yet.

The floods, however, have come back again and again over the years, with increasing frequency and ferocity, twice in 2005, again in 2006. The following year, the “worst storm ever” flooded three thousand acres of black dirt farmland, prompting one farmer to say, “I can handle competition, but farming on a riverbank is farming next to a terrorist, and I can’t handle that.” The farmers again appealed to the DEC and to the Army Corps for help. Then came hurricane Irene and tropical storm Lee in 2011 which put some of the farms under fifteen feet of water. Governor Cuomo came to the black dirt to survey the damage of the two storms, acknowledge the important work that farmers do, and assure them that “we are doing everything that we possibly can do.”

State and Federal financial aid was handled through the Wallkill River Maintenance Agreement that the Army Corps and the DEC had established in 1987 with Orange County and the townships of Goshen, Minisink, Warwick, and Wawayanda. Under the arrangement, the County was charged with clearing and stabilizing a twelve mile reach of the Wallkill River from Oil City Road on the New York and New Jersey border in the south, to county route 37 and the Pellets Island Bridge in the north. The DEC established the scope of the work and performed oversight.

Over the years, farmers have grown more frustrated with the government’s lack of commitment. State elected officials have promised more money for flood control, but have provided only enough to finance small mitigation projects, not the dredging and channel straightening that many of the farmers see as the only longterm solution. While they wait for the Army Corps, the farmers have been aggressive in promoting whatever short term flood control projects are offered to them. They have taken the initiative in suggesting new flood mitigation plans, like utilizing idle land in the river’s flood plain to absorb rising waters. “The farmers are the guys out there every day and know the drainage issues better than anybody. We see different things and know how the water flows,” a black dirt farmer told the NY Farm Bureau in 2013.

The farmers also felt that the County was moving too slowly on the channel maintenance work. Eventually, administration of the project was turned over to the Orange County Soil and Water Conservation District. The OCSWD had produced the Wallkill River Watershed Conservation and Management Plan in 2004, which advocated for broad based and intelligent watershed planning. The report they wrote attempted to address all the major concerns of communities up and down the length of the Wallkill.

Even while considering the health of the entire watershed, the OCSWD was still very sympathetic to the concerns of the black dirt farmers. They acknowledged that poorly run farms can hurt the environment, citing the pesticide pollution of the Wallkill as one example, but they also realized that well managed farms provide better protection for fresh water and wildlife than any other land use. Their Wallkill River management plan, therefore, supported “continued efforts to implement flood control measures for protection of the Black Dirt agricultural lands.”

Orange County Soil and Water acknowledged that there were going to be periodic floods no matter how wide or deep a channel was dug. The slope of the valley floor was too shallow to avoid such occurrences. Their overarching goals were to do what they could to help the farmers control flooding, and at the same time, enforce practices that would help restore the river’s ecosystem, and conserve the soil and water.

Recently the OCSWCD and the Wallkill Valley Drainage Improvement Association have been trying to persuade the County and the State to extend the boundary of the 1987 drainage agreement another two miles north from the Pellet’s Island Bridge to route 17M. This way they would be able to stabilize more of the channel and keep it free from brush and debris, just as they had from Pellet’s Island south to New Jersey.

Moving the boundary north makes perfect sense. Anyone acquainted with the history of this corner of the world knows that the Cheechunk Canal bypass is crucial to the drainage of the entire valley, but because of the arbitrary boundary, the reach north of the bridge has become overgrown with vegetation and debris which blocks the water’s flow. Channel clearing further upstream has little effect if the water course near old Outlet is backed up. All of this was common knowledge in the 1840s. Why wasn’t that knowledge applied in 1987 when the maintenance agreement was made and the boundaries were drawn?

The Pellet’s Island Bridge boundary line was drawn only one half mile upriver from the Orange County Landfill when the waste site was in full operation and breaking laws on a daily basis. In the 1980s trucks owned by mob carters were often lined up at the landfill gate. Payoffs were being made, tickets were being squashed, and environmental regulations were being violated. Two independent witnesses testified that around 1986 and 1987, they saw county workers pumping landfill leachate down the river bank and into the Cheechunk, and that the violations were being committed with the knowledge of sheriff’s officers and the New York State DEC.

It is not unreasonable to suspect that the arbitrary Pellet’s Island boundary was drawn by the County and State to keep other parties from getting close to the landfill, particularly its backdoor on the canal where illegal activity was taking place. Not surprisingly, the County and State still don’t want anyone getting too close. The OCSWD’s recent efforts to have the drainage management boundary moved north have been met with resistance. Questions they asked more than a year ago have not been answered. “Current thinking is to exclude the landfill area,” one frustrated board member observed a month later. “The County feels if it goes to that part of the reach, the DEC might tell the County to fix the bank.”

As of this summer, it was still unclear to Soil and Water’s board whether the landfill side of the stream would be included in the boundary extension. “It should be for effectiveness of maintenance activities,” one member stated, “but the sensitivity of this area comes into play.” The river bank along the landfill is extremely sensitive, sloughing into the Cheechunk and leaking chemicals. But is it the environment’s sensitivity that primarily concerns the County and the State, or is it the politically sensitive history of the landfill and their current lack of effort to maintain it properly?

The black dirt farmers are more observant of the Wallkill and its floods than any other interest group, and to their credit, they are the most outspoken. But they have nothing to gain by calling attention to the landfill. If they do, they run the risk of slowing down their drainage efforts. The landfill, if properly addressed, could easily delay any further dredging attempts because the landfill is unstable.

Concerns about the landfill have been expressed by environmental activists like Michael Edelstein, president of Orange Environment, who calls the Orange County and Al Turi landfills ticking time bombs. Edelstein knows his history. “This landfill property is literally sitting right in the most crucial place for water evacuating from the Wallkill.” He is worried that the heavy mass of garbage in the unlined landfill could “breech the outer wall and ooze into the canal, thus pinching off the waterway.”

Yet, the State of New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation and the Government of Orange County, the two entities charged since the landfill closed in 1993 with monitoring and maintaining the site, appear to have been negligent in their duties. In 2012, the DEC cited the County for poor management of the landfill and failure to comply with reporting requirements. According to the DEC, a new reporting procedure that had been implemented in 2004 was not being followed by the County. The letter sent to the County’s Deputy Commissioner for Public Works was a reminder that, “The County has not complied with its legal obligations regarding the operation and maintenance of the landfill site nor the associated reporting obligations required by the Consent Order.”

Despite correspondence going back and forth since then, progress has been slow. The DEC determined in early 2013 that the seeps coming out of the bank below the landfill were impacted with landfill leachate. But a few months later the County was still on record stating that “the data does not indicate a release from the landfill has or is currently occurring.” Unsurprisingly, therefore, they had no plan in place for dealing with the seeps.

As recently as September, the current Orange County Executive, Steve Neuhaus, dismissed claims that landfill leachate was seeping into the Cheechunk. “These are the ghosts of landfills long ago and if there is any leachate it will definitely be addressed.” Given the recent communication between the State and County establishing that the seeps along the Cheechunk contain leachate, and given the established history of leachate seeps along the canal dating back to 1976, the County official’s remarks appear to be disingenuous.

Presently, it is anticipated that the revised Seep Mitigation Plan could be submitted by the County as soon as December 2014. In the meantime, any attempts to address the sloughing of the banks as the landfill slides toward the canal have been postponed until after “addressing the leachate seeps.” Inclinometers that had been installed to determine if the bank is shifting are no longer functioning.

In other words, little has been done to address the problems so far. The State has cited the County again and again for failure to maintain the landfill, but there are no repercussions for violations, and conditions remain the same. While the two governments continue stalling, other groups have been pressing for action. Farmers pushed Orange County Soil and Water to undertake the Pellet's Island channel clearing project south of the boundary and in the vicinity of the landfill. The results have been mixed. Brush and small trees were removed from the bank opposite the landfill, but there have been questions about the project’s effectiveness. Additional questions about authority and jurisdiction have dogged the project as well.

Another group pushing for solutions has been Orange Environment which commissioned a biological study of the Wallkill River in the early 1990s. Looking at both the health of the ecosystem and the drainage problems plaguing the black dirt region, their report suggested exploring long term remedies. “Restoration of the Wallkill to its original meandering channel would greatly enhance the stream quality there and downstream.” In addition to putting the Wallkill back into its original channel, the study also suggested the creation of wetland buffers along the channel to absorb and clean flood run off.

This, then, is the scene of the impasse. We are in trouble if we do nothing. The farms will continue to flood, and more farmers will be forced to sell. The landfill will succumb to erosion and gravity and settle into the river. On the other hand, aggressive channel dredging runs the risk of speeding up the pollutants that are heading downstream, and further runs the risk of destabilizing the landfill. And just to complicate things, major development projects are encroaching on this contaminated and archaeologically sensitive area. Despite objections, developers are planning a factory, close to the Al Turi landfill and the dried up Cheechunk Springs, that will produce vegetarian convenience foods for an international market. Many of the competing views, claims, and solutions being offered today are reminiscent of the long ago Beaver and Muskrat conflicts over the same stretch of flowing water.

Now is the moment to be seeking a seven generation solution that fairly and inclusively addresses the problems posed by this location. If the Army Corps of Engineers is indeed conducting a study to come up with a more permanent plan, they must look at the whole picture and take the two closed and leaking landfills into consideration. The County and the State must take their responsibility for the canal and county landfill seriously, and be more forthright about the problems the landfill poses. This is our greatest challenge: to act like the past has something to tell us, and the future really matters.

In the Lenape language, the word cheechunk translates as either mirror or soul depending upon the regional dialect. We might do well to take this hint and search for our own reflection in the Cheechunk. Looked at correctly, the three mile stretch of waterway that we have been considering can serve as a mirror into who we are, where we’ve been, and what we are becoming. You can learn a lot about people by observing the way they treat their land.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed