Part 2: The Federal Connection - How the Task Force produced the Federal Connection; a summary of the report with the help of one of its authors; implications for our time.

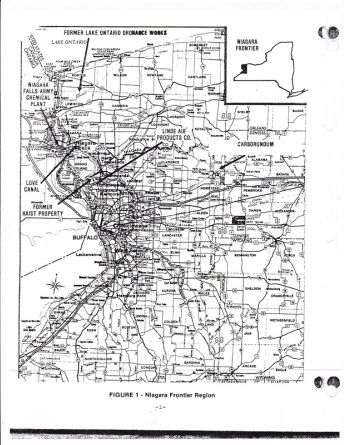

Location of Manhattan Project and Chemical Warfare Service sites in the Niagara Falls Region

“Rub a dub dub for Rocky Flats and Los Alamos, Flush that sparkly Cesium out of Love Canal…” Alan Ginsberg,1980

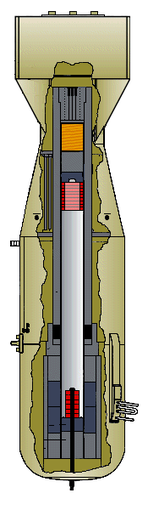

Little Boy

Little Boy In fact, the total amount of uranium 235 required to build Little Boy, the bomb that had been dropped earlier that day, was less than 150 pounds: 86 for the bullet, and 57 for the trigger with which the bullet collided. But it had taken extraordinary effort to produce this one armful of enriched uranium. In its natural state, the richest ore contains only about 1 in 500 parts uranium, so the ore first had to be chemically refined to pure uranium. The uranium metal that is produced during refinement is made up of more than 99% uranium 238. Only the rare uranium 235 isotope, with its unstable nucleus, can be used to produce the rapid fission reaction required for the bomb. Therefore, the refined uranium metal next had to be enriched through a series of steps using heat, gaseous diffusion, and particle accelerators to separate the lighter uranium 235 from the heavier 238.

The scientists of the Manhattan Project had to be provided with enough 90% pure uranium 235 to reach what they called critical mass, that is, the amount of uranium necessary to guarantee a chain reaction of neutrons splitting atoms, releasing more neutrons splitting more atoms, leading to the explosion of energy that the scientists desired - all within a trillionth of a trillionth of a second. As it was, Little Boy was something of a dud with only about two pounds, or about 1.5%, of its enriched fuel undergoing fission before the detonation blew apart all the remaining material. Fat Man, the bomb dropped over Nagasaki three days later, was triggered by plutonium and was much more effective.

According to the President, all of this was accomplished with very little risk to the men and women who worked in the plants. “Although workers at the sites have been making materials to be used in producing the greatest destructive force in history, they have not themselves been in danger beyond that of many other occupations, for the utmost care has been taken of their safety.”

Truman mentioned a few of the atomic production sites, like Tennessee, Washington, and New Mexico. He did not mention the plants in the Niagara Falls Frontier or their role in refining the uranium that was passed on to the other Manhattan Project sites. Perhaps he did not mention Niagara because the work that was performed there doesn’t capture and excite the imagination the way diffusion plants, breeder reactors, and testing laboratories do. What happened at Niagara Falls was basic, brute and earthy. The work was dirty, loud, foul smelling, sometimes dusty, sometimes steaming. Tons of raw ore were pulverized, bathed, drained, precipitated, and baked.

Even though the Niagara Region’s role is not as well known as those played by Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, or Hanford, all of the sites shared a similar history, and contended with similar problems and policies. And just like the other Manhattan Project sites, the Niagara Frontier is still contaminated with radiation. The problem at all of the sites has been compounded by the policy of secrecy that Truman identified back in 1945, and that has remained with us ever since. Much of what the Manhattan Project did and much of what it left behind is still unknown.

After an intensive 20 month investigation, the Task Force submitted their findings to the Assembly in a lengthy report, The Federal Connection: A History of US Military Involvement in the Toxic Contamination of Love Canal and the Niagara Frontier Region. The Report boldly contradicted the Army’s contention that it was not responsible for any contamination. It told the story instead of “an incredible, occasionally surreal, history of federal mismanagement, exploitation, and despoliation of widespread sections of one of the most beautiful and productive regions of New York State.”

The report claimed that the Army had misled workers and put them in danger, conspired with industrialists to deceive local officials and the public, and ultimately put the entire population at risk with its carelessness and subsequent cover ups. The Task Force, in other words, had not come to the same conclusion about the triumph of science, industry, and Government that Truman had reached. Instead, they accused the US Government of a criminal cover up.

Today, in the year 2014, thirty five years after the Task Force investigation which came thirty five years after the war, A.J. Woolston-Smith, or Smitty as he is usually called, still talks about The Federal Connection and his investigations around Niagara Falls. Sometimes he comes to visit me at home, and we sit across from each other at the kitchen table to have what Smitty likes to call a chin wag, or a long chat. He stopped in one afternoon a few weeks ago, and we talked until well after dark about his work with the Task Force.

“The people in Niagara Falls knew they had been screwed. They knew they were war victims too,” he told me. “All of the Niagara Falls Frontier looked run down back then, around the time of Love Canal. It looked depressed. Exceptionally depressed. There was high unemployment in the late 1970s. The roads were torn up and potholed. Some of the factories along Buffalo Avenue were still open, but barely open. There was only a whisper of smoke coming out of the stacks. Hooker and DuPont looked dilapidated. There were sheds and empty kennels near many of the plants. These used to be filled with guard dogs.”

A.J. Woolston-Smith, Smitty

A.J. Woolston-Smith, Smitty When Stanley Fink, the next Assembly Speaker, appointed Kingston Assemblyman Maurice Hinchey to chair the Task Force, he assigned A.J. Woolston-Smith to go along as investigator. The Manhattan project had been a joint venture between the US and England with limited participation by Canada. Smitty had contacts in the military of all three nations. He was just the man for the job.

“You know,” Smitty told me with a wry smile, “All of these people in the atomic establishment have a pretty high view of themselves, but we could see that they had made a mess of everything and were taking no responsibility for it.” I asked him if he had ever been scared of the Feds because of the work he was doing back then, or if Hinchey was frightened that he might be destroying his own political future. “No,” he shrugged and said. “We just bashed on. Maurice thought it was important that the people knew the truth.”

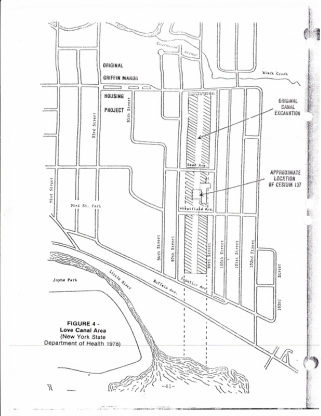

Job number one for the Task Force was to determine if the Army was responsible for any of the contamination at Love Canal. Accordingly, Smitty began his work by talking to the neighbors. “I went to talk to various people in the Town of Wheatland and the City of Niagara Falls, and the people who had operated the bulldozers at Love Canal. Town maintenance workers. They told me about the pig men and everything else. The Army had not talked to many of these people when they conducted their own investigation a year earlier.”

According to The Federal Connection, the eyewitnesses with whom Smitty had spoken established, “conclusively that Army personnel openly, concertedly and repeatedly disposed of drummed materials at Love Canal.”

One eyewitness, Ms. Lucinda McCombs, testified before the Task Force that her children had come running into the house after playing near the Canal one day to tell her about “funny men” with “faces that looked like pigs” down by the Canal. She ran out to see for herself and saw “brownish green colored trucks” and men “with the same colored clothes, except that they wore gas masks, and they were dumping containers into the Love Canal.”

A similar story was told by Mr. Alfred Jones who testified to the Task Force that he used to swim in Love Canal during the summer of 1942 when he was 12 years old. One time he saw “an army two and a half ton truck” with soldiers on it dumping drums into the Canal. It was the only time he saw it happen, but he remembered it vividly because the next time he went swimming, his “skin started burning, and whether it was caused by them or not, the chemicals whatever… we had to quit swimming because it burned our skin.”

Another witness, Ms. Mary Wahl, reported seeing Army vehicles as well as numerous trucks owned by private companies going into Love Canal in the early 1940s. She said that many of the trucks were red colored Hooker trucks, and that a few were from Mathieson Alkali, but that “dozens” were “green-colored, open-backed trucks with the words ‘Army Ordnance’ written on the doors” and “always carrying at least two armed soldiers.” The trucks rolled by her house slowly. She never followed them down, but she noted that when the trucks went in, “they were loaded with drums,” and when they came out, they were empty. Children who went down to the Canal to play told her that armed soldiers told them to “stand back” because they had chemicals there.

Ms. Wahl remembered watching out for the titanium trucks that came once a week because they kicked up a fine powder that made it very difficult for the neighbors to breathe. But she also testified that her neighbors had grown numb. “At night you’d hear these big explosions. We used to say, there goes the Canal again and we would all go back to sleep… It got so the firemen did not even bother.”

Mr. Ruben Licht, a former Army staff sergeant and DuPont employee, testified that on several occasions he followed Army trucks into Love Canal in 1946 or 1947. According to Mr. Licht, they were green trucks with removable wooden stakes on the sides and a white star on the door, and “usually carried four soldiers. Two soldiers guarded the end of the roadway leading to the Canal, while the other two rolled the drums off the truck and pushed them into the Canal.” He also testified that on one occasion he approached the truck, and the guards told him not to go any further. He recalled being surprised that the men were wearing side-arms in peace time.

There were other witnesses who told the same stories with the same details. Mr. Arthur Tracy was able to identify some of the trucks that were dumping at Love Canal as the same trucks that were parked at the Niagara Falls Chemical Warfare Plant on Buffalo Avenue.

“I kept doing interviews and locating installations in Niagara,” Smitty told me. “MIT chaps and others knew what was going on there. Many people knew. At first, people were reluctant to talk to me. I made them understand that I was not out to get them. A lot of the people around Niagara were afraid that the Government was going to come after them, especially after the stand off in the spring of 1980. That’s when some of the Love Canal residents held two EPA officials hostage for several hours, demanding that President Carter evacuate all the families from the contaminated area. The residents were soon surrounded by FBI agents who looked like they were going to arrest them.”

“But the people’s greatest fear was of what lay underground or in their drinking water. By the time we were doing our investigations in late 1979 and 1980, health problems were starting to crop up: miscarriages, blood diseases, rashes. People were already starting to notice cancer clusters in the neighborhood. Their fear of radiation and contamination was greater than their fear of the Government.”

“But even more than fear,” Smitty continued, “a lot of the people were angry. Now that they were figuring out what was going on, and what had been done to them, they were mad at the politicians.”

Smitty recalled going from house to house, talking with the homeowners and getting their stories. “I spoke with the many complainants in the Love Canal neighborhood about their basements filling up with black stuff. Lois Gibbs, the leader of the neighborhood group, talked to other Task Force people about the black ooze in her basement. One time she was talking to a bunch of her neighbors, telling them that ‘there’s a fellow going around here who knows everything.’ She was talking about me, and didn’t know who I was or that I was standing right next to her.”

“The black ooze was really something,” Smitty recalled. “I got the stuff on my fingers once. They were doing remedial work at the Canal. Approved by the EPA. Water and black ooze were being pumped out of Love Canal into another channel under the road where it flowed into the Niagara River. I put my hand in the water, and the black ooze was hot and burned.”

Among the interviews that impressed Smitty the most were the ones that he did with “the Love Canal Gang”: Donald Harris, Fred Downs, and the Jones brothers, William and Lawrence. All four were young boys in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and they used to play and swim near the Canal when the weather was warm. Their individual testimonies, though given separately and many years after the fact, were consistent with each other. The details that they remembered had obviously made deep impressions on them. They recalled the trucks and jeeps that came down to the edge of the Canal, the soldiers who were in them, and the heavy white gloves that the soldiers wore. They remembered the odd shaped barrels and how the Army men handled them gingerly, and how the men approached the boys and chased them away.

One of the Canal Gang boys, Fred Downs, testified that one time when the Army vehicles came down to the Canal there was an argument. “I remember that there was swearing between the Army guys and a man that was not in the Army who operated the machinery. It appeared that this was not part of the man’s job or he was not getting paid for it or something like that.” The man that Fred was probably referring to was Frank Ventry, a bulldozer operator. It was Ventry’s testimony that finally convinced Smitty.

Frank Ventry had operated a bulldozer at Love Canal in the late 1940s for the City of Niagara Falls. He testified that on one occasion an Army truck arrived at the Canal accompanied by a jeep carrying a captain who was wearing a sidearm. Ventry was on the other side of the Canal, pushing dirt with his bulldozer. The captain ordered him to approach. But as a former combat engineer with no love for captains, Ventry refused. “The Canal was wet, and kind of soupy and I didn’t like to walk in it and neither did he.” The captain sent a sergeant over with the message: “He wanted me to make a pile of dirt, soft dirt, so he could unload the drums without injuring them and I did that. That is how I remember the Army dumping there.”

He went on to describe the long heavy gloves that the men wore, and the odd beer keg shaped drums that were being gently unloaded. He was asked to bury the drums in the deepest part of the Canal. He was told that the truck came from the Chemical Warfare Plant on Buffalo Avenue.

On many occasions, Assemblyman Hinchey accompanied Smitty as he did his investigative work around Niagara Falls. “The interviews with the people were what moved Maurice Hinchey,” Smitty recalls. “He was inspired to action by their voices. He took to heart the stories they told us, and it motivated him to push on with the investigation. I think that the time we spent up there established the pattern for what he continued to do as an Assemblyman for the rest of his time in Albany. He later held quite a few public hearings that investigated organized crime, and he relied on the testimony of people who were living it, witnessing it, being hurt by it.”

Maurice Hinchey

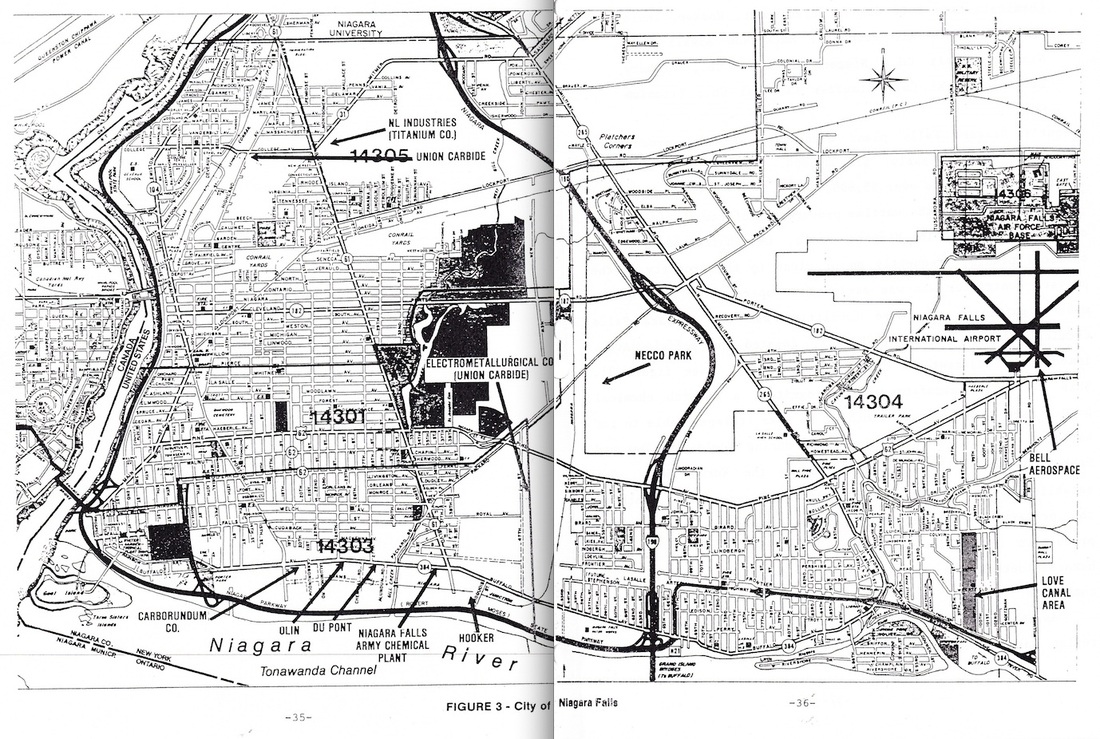

Maurice Hinchey The Task Force compiled a list of Manhattan Project and Chemical Warfare Service sites around Niagara Falls, along with an inventory of the wastes that they had generated. They wanted to see if the toxins that were produced in the MED and CWS plants matched up with the chemicals that were showing up in Love Canal.

- The Niagara Falls Chemical Warfare Plant (NFCWP), operated first by DuPont and then by Hooker, manufactured impregnite for the Army.

- The Northeast Chemical Warfare Depot stored war materiel on the site of the former Lake Ontario Ordnance Works (LOOW).

- The Thionyl Chloride Plant, operated by Hooker, manufactured reagents for the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS).

- The Dodecyl Mercaptan Plant, operated by Hooker, contributed to the production of synthetic rubber for the Rubber Reserve Company, paid for by the government-sponsored Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

- The Hexachloroethane Plant, operated by Hooker, contributed to the production of smokescreen for the CWS.

- The Arsenic Trichloride Plant, operated by Hooker, produced chemical warfare gas for the CWS.

- The P-45 Plant, operated by Hooker, shipped tank cars of hexafluoroxylene to Oak Ridge for the Manhattan Project (MED).

- The Ceramics Plant, operated by Linde Air, processed uranium ore to uranium oxide then to uranium tetrafluoride for the MED.

- The Electrometallurgical Company Plant, owned by Union Carbide, converted uranium tetrafluoride to uranium metal for the MED.

“I asked a lot of questions,” Smitty explained to me, “and found out who owned what property, and often it turned out to be the Manhattan Project or the intelligence services. I learned all of this from people who lived or worked along Buffalo Avenue. Maurice and I also talked to municipal officials, and I would go through town records to look at deeds and ownership records.”

“People knew that it was all secret government work that had been done in those factories, and they knew it was hazardous. The dogs gave it away. The people would tell us, ‘you always saw soldiers and guard dogs at the plants.’ The people knew that something was going on and that it all had to do with the war.”

“We wanted to take a close look at the plants on our list and show what kinds of materials they produced as well as what kinds of waste. We also wanted to determine how deeply the Army was involved in the process of disposing of that waste. We wanted to see how much the Army knew about what was going on in those plants.”

I asked Smitty if he was surprised by what he found. “Oh yes. The list of plants that we made was a work in progress. We kept discovering more and adding them to the list. The Army didn’t just hand the list to us. They denied things, like manufacturing phosgene during the war. We had to find it out for ourselves.”

The first plant that the Task Force explored in The Federal Connection was the Niagara Falls Chemical Warfare Plant on Buffalo Avenue. The DuPont chemical company operated the plant for the Army from 1942 until it closed in 1945, manufacturing impregnite, a substance with the code name “CC-2.” The Army impregnated uniforms and protective clothing with the secret chemical compound to make the wearer impermeable to gas warfare attacks.

Until the end of the war, the NFCWP flushed all of its liquid wastes down the sewers despite the objections of city officials and neighbors. The "liquors" emitted noxious chlorine and acetic acid fumes that killed all the trees and shrubs around the factory. For every 100 pounds of impregnite that were produced, 48 pounds of this highly toxic liquid waste were also generated. Solid wastes containing the same toxins were packed into thousands of 55 gallon drums and hauled by DuPont to one of their own nearby landfills, Necco Park.

This arrangement changed during the Korean War, however. From 1951 until 1953, Hooker Chemical re-opened the Niagara Falls Chemical Warfare Plant for the Army in anticipation of more war time demand for impregnite. Hooker, like DuPont, dumped their liquid wastes down the sewers, but they dumped their drummed wastes into their own landfill, which happened to be Love Canal. The Task Force determined that much of what Hooker dumped into Love Canal was done under contract for the Army.

All of the chemical wastes generated at the NFCWP were found in samples at Love Canal. Of particular interest were the anilines, like chloraniline, chloroaniline, and dichloroaniline, signature chemicals that would not appear in Love Canal for any other reason than as by products of impregnite production. The Army had access to the same lab results in 1978 that the Task Force later used, yet the Army had failed to make the obvious connection between impregnite production and the aniline wastes in Love Canal. When questioned about this later, one of the Army investigators replied that he didn’t remember seeing any of these chemicals on the list.

The Task Force was learning quickly that federal record keeping was haphazard or nonexistent. No one had ever done a similar inventory of the chemicals manufactured and the wastes generated in the Niagara Frontier’s war plants. The Task Force had figured out that much of the toxic waste in the region had been generated in Government owned and Government equipped plants that had produced material exclusively for the Government. The lawyers on the Task Force argued that the Government was clearly liable for any damage to health and the environment.

But at the same time, the more the Task Force learned, the more questions they couldn't answer. The most disturbing question of all was this: “The documents revealed that the Army Ordnance Department, the Chemical Warfare Service and the Manhattan Project were all heavily involved in chemical production and uranium processing in the region. What, then, had become of the chemical and radioactive wastes these projects necessarily had produced?”

For a year, Smitty dug into boxes and files. He visited the National Archives as well as the Center for Military History in Washington, D.C.; the National Federal Records Center in Suitland, Maryland; the Edgewood Arsenal in Aberdeen, Maryland; headquarters of the Army Corps of Engineers and the General Services Administration, both at Federal Plaza in Manhattan; the records of the City of Niagara Falls, of New York State, the Niagara County Clerk’s office, and the records of corporations like Hooker, DuPont, and Linde Air.

Smitty remembered, “I was going back and forth from Niagara Falls to Albany and sometimes to Maryland and other federal records depositories. Everywhere I went, the archivists were cooperative. Do you know what? They wanted me to know what happened. They helped me find the records I was looking for. It didn’t hurt that I was a veteran and had been in the service during the war. But people wanted me to find things out. They wanted it all known, all this business that happened during the war. One archivist told me that I was on the side of the angels. The reason was because the problem was enormous, and no one was doing anything about it.”

Immediately after World War II, the military had to dispose of mountains of surplus war materiel. A great deal of it was highly toxic. Bases were closing, and large inventories of poisons and useless weaponry had piled up in many of them. All too often, nothing was done with the surplus, or the wrong things were done with it. Poisonous gases and radioactive wastes were dumped into the ocean. Radioactive and chemical wastes were left unattended, contaminating both air and water. A 1948 Chemical Corps Disposal Manual instructed soldiers how to dispose of excess impregnite. One is told to either scatter it on the ground and wait for the rain, or bury it in a pit at least three feet deep, or burn it on a day when the wind will carry off the chlorine gas.

The root of the problem, according to the Task Force, was “the War Department’s inability or disinclination to allocate sufficient funds for the storage of toxic agents or for their proper disposal.” It wasn’t until people in various parts of the country started injuring and killing themselves by accidentally stumbling upon, and setting off, abandoned and forgotten mustard gas canisters, contaminated pipes, and unexploded warheads, that the Army began to realize that it had a liability problem. Only then did the War Assets Administration begin to show some restraint in the way it disposed of contaminated properties - but not very much restraint.

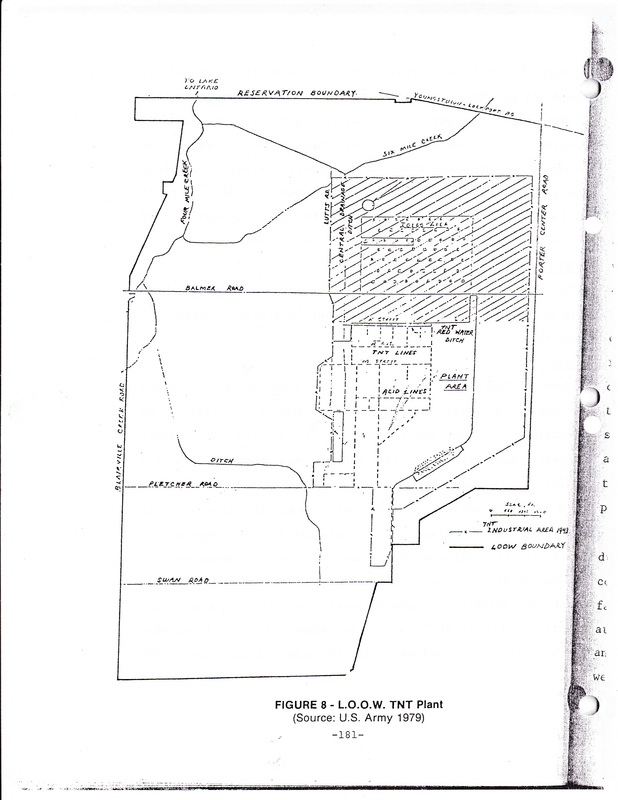

In the Niagara Frontier beginning in 1944, surplus and contaminated war materiel was shipped to the Northeast Chemical Warfare Depot, the second site on the Task Force’s list. It was built on the LOOW, the former TNT manufacturing plant that had operated for only nine months in 1942. The scattered buildings and igloos that had been used for TNT production and storage became the resting place for incendiary bombs and other military throw aways. Impregnite found its way into the depot too, since far more was produced than was needed during the war, past experience having proven to be an ineffective guide. The Task Force speculated that impregnite from the storage depot might have been dumped in Love Canal, since the white powder packed in white cardboard canisters matched the descriptions supplied by several eyewitnesses.

The Task Force soon learned that the Army was using the same sloppy practices at the other sites on Smitty’s list, not just the LOOW. Hooker’s thionyl chloride plant generated large quantities of highly toxic and explosive toluene solvent wastes along with thionyl chloride residues in the production of phosgene, which was like mustard gas. These wastes were packed in over sized drums and hauled to the Hooker landfills including Love Canal which opened in 1942, the same year that the plant opened. In all likelihood, these were the drums that the boys in the Love Canal Gang watched the soldiers push into the Canal, and that Frank Ventry buried in the deepest parts. They may also account for the explosions that Mary Wahl and her neighbors heard at night.

The top secret, heavily guarded P-45 plant was built in 1943 and was code named “the bra factory” in order to confuse it with another military plant named P-45 which manufactured undergarments for female soldiers. It was operated by Hooker and generated both drummed and liquid waste. The liquids went down the sewers, and there are no records of what happened to the solid wastes. Next door to P-45, the MED built another plant whose sole function was to remove a whitish oxide from uranium slag that had been sent over from the Linde plant. After the slag was washed with hydrochloric acid, it was sent back to Linde. The waste, however, went into the sewers, tiny radioactive particles included.

The Electromettallurgical Company which converted uranium tetrafluoride into uranium metal also generated a liquid waste that was slightly contaminated with uranium. It too was poured into the sewers. “We were seeing a pattern. There was no accountability when it came to disposing of all of this waste,” Smitty said. “And there was a lot of waste.”

The Task Force believed that they had also solved the mystery of how cesium made its way into Love Canal. The radioactive isotope, cesium 137, showed up in a radiological survey of Love Canal performed by the New York Health Department at around the time of the first clean up. It was located in a large concentration behind the 99th Street School. The cesium was found in soil that was different from the surrounding soils and relatively close to the surface.

Cesium 137 does not appear anywhere in nature. It occurs as a result of fission experiments using uranium or plutonium. Such experiments were carried out at the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory in Schenectady, NY, a MED site. Surplus cesium 137 from Knolls was stored at the Chemical Waste Depot at the LOOW. As a result, there were traces of cesium 137 all around the LOOW. While the Task Force was not able to prove it, the best hypothesis for how cesium 137 got into Love Canal is that fill from the LOOW was used as cover after pits were dug to remove barrels of waste near the 99th street school adjacent to the Canal.

“We had taken things as far as we could,” Smitty told me. “We had witnesses, we had documents, and we had the inescapable fact that the chemicals that were showing up in Love Canal matched the waste streams of facilities that had been operated for and by the Army during the war. The only thing we could do next was point out how sloppy the Army had been, or rather, how cavalier they had been about the whole matter.”

The members of the Task Force had realized that the Army was thoroughly involved in widespread contamination, most of which was never acknowledged, recorded, or shared with State or local officials. Based on their findings in the early stages of their investigation, they concluded that the Army had not done a credible investigation of itself.

The Army had conducted its investigation and wrote its report on the insistence of Congressman John Lafalce in 1978, shortly after Love Canal first began making headlines. The entire Army investigation took only three weeks. The Task Force maintained that an adequate investigation could not possibly be performed in that short amount of time. The Army had employed, “hectic, haphazard methodology.” The Federal Connection concluded that, “The Army’s investigative emphasis, it seemed, was not on uncovering new evidence, but on refuting the old.” The Army did not do a thorough examination of records, nor had they sought out additional witnesses or people with knowledge. They also did not review their own witness interviews, never following up on what had been told to them by Frank Ventry, the bulldozer operator.

World War II poster

World War II poster Most incredibly, the Army did not look at any activities of the Manhattan Project when it conducted its investigation and wrote its report. They argued that it was not their job to include the MED since the Manhattan Project records had been taken over by the Atomic Energy Commission.

The Army argued several times that it had “no involvement” in the contamination of Love Canal. The claim was made in their 1978 report, and it was made again in response to a preliminary findings report from the Task Force. The Task Force members knew that the Army’s assertions were not true. They wanted to show next just how deeply involved the Army actually was in the maintenance of the plants and toxic waste disposal. To that end, the next section of The Federal Connection demonstrated in vivid detail how the Army and managers of Linde Air Products conspired together to dispose of 37 million gallons of radioactive waste in underground wells. The Task Force hoped the story would serve as an example of how the system worked as well as the Government’s culpability.

A Freedom of Information Act request made by the Task Force led them to their startling discovery about the Linde wells in documents from the Manhattan Project archives. They learned that the radioactive dumping took place from 1944 to 1946 in the shallow wells on the Linde Air Products site in Tonawanda. Based on the documentary evidence, the Task Force concluded that, “MED officials, all Army personnel, were intimately involved in the decision making regarding the disposal of these liquid wastes.”

The documents also proved that both Linde and MED officials were well aware that injecting the waste “would permanently contaminate Linde’s wells and probably the wells of Linde’s neighbors in the surrounding region.” The most damning conclusion, however, was that, “This method of disposal was selected precisely because the source of the underground contamination could not readily be traced back to Linde or the Army.”

Throughout the time that the Task Force was doing its work, no one had ever mentioned those wells. No one had indicated that they even existed. Yet both the Army and Linde had been intimately aware of them. “The very existence of the Linde wells seems to have slipped through some crack in the bureaucratic structure to evade detection,” The Federal Connection concluded.

The Task Force did not pull punches in their report: “Reviewed in chronological perspective, these documents provide a fascinating ‘micro-history’ illustrating the manner in which Manhattan Project policies regarding the problem of waste disposal were executed in the Niagara Frontier Region. The classic ingredients are all present here - the continued use of untried methods and primitive technology until the threat of financial and environmental ruin became a reality; the pressing demand for uninterrupted production, at any cost; and, at every stage, the tightening of the purse strings when it came to providing adequate funds for safe disposal.”

Linde had experience in the ceramics business, working with uranium ore which was used to make the salts that were used in the production of ceramic glaze. Linde’s role in the Manhattan Project was to take tons of uranium bearing ore, both American and African, refine it down, then move it on to the next processing plant. Refinement was done in three steps. Step one produced a black oxide, which was sent to Hooker for an acid bath, and was then sent back to Linde. Step two produced a brown oxide, or uranium dioxide, and step three produced uranium tetrafluoride, a green salt, which was sent to Electromet.

Step one commenced at the Linde ceramics plant in July 1943 and continued until July 1946 when supplies ran out. By the time they were finished, Linde had produced 2,248 tons of black oxide which also meant they generated about 8000 tons of uranium ore sludge containing .54 percent uranium. Most of this solid, slightly radioactive sludge was hauled to the nearby Haist property where it was dumped and buried and started leaching toward the Niagara River. In 1960 the Government sold the Haist dump to Ashland Petroleum which then built a tank farm on top of it.

The sludge from the higher grade African ore was sent to the LOOW for storage. Together, the sludge and residues at both sites and those at the ceramics plant, which the Manhattan Project sold to Linde after the war, contained approximately 107,000 pounds of uranium.

While the solid sludge generated by step one can be accounted for, there is no record or trace of the “highly caustic radioactive liquid wastes that were flushed down the wells.” When the plant first began production, the liquid was discharged into the City of Tonawanda sewer system. City officials soon got into a battle with Linde, that lasted through April 1944, because the caustic radioactive discharge was affecting the acidity of the water. Linde had to find another way to dispose of the liquid after the City threatened to “bulkhead the Linde sanitary sewer entirely.”

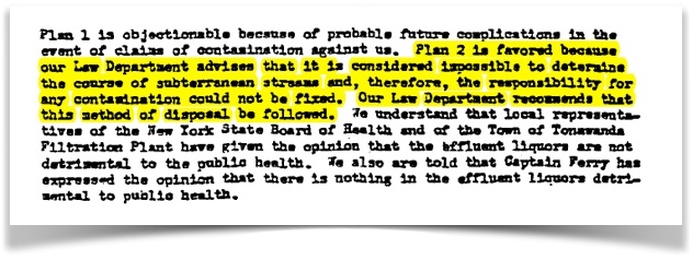

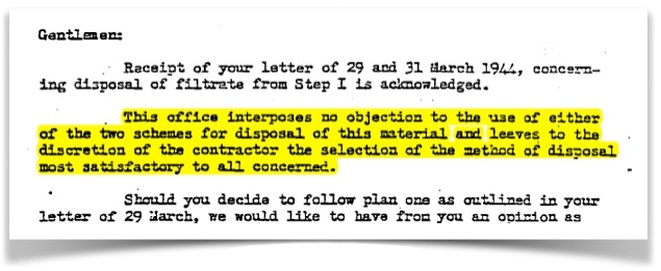

Linde had two options. The first was to discharge the liquid into the storm sewer, as opposed to the sanitary sewer, where it would empty into Two Mile Creek, pass through a public park, and then into the Niagara River. The second option was to pump it into underground wells that Linde had drilled to supply cooling water, but that were found unfit for use. Linde eventually ended up doing both.

In an extraordinary letter, from the Assistant Superintendent of the Linde Plant to the Army, the two alternative methods of disposal are presented, and the first option - the sewers - is discounted because “of probable future complications in the event of claims of contamination against us.” The Linde official went on to advocate for the second plan - the wells - because, “It is considered impossible to determine the course of subterranean streams, and therefore the

The reply from the Army, signed by Captain E. L. Van Horn, Army Corps of Engineers, is even more extraordinary in that he told them to choose whichever option they wanted. He had no objections. But then he went on to write, “… even though we might not be liable from a legal standpoint, we might from an ethical point of view be doing something which will effect the production of other war plants, and could be severely criticized for our actions.” The War’s

The Task Force demonstrated that Linde and the MED misled City and State officials about the composition of the caustic liquid they had been flushing down the sewers. The Army and Linde had neglected to make any reference to the particles of uranium oxide. Failure to mention the radioactivity was typical of the MED’s policy of concealment. The MED always divulged as little as possible.

“Linde’s neighbors were not asked their opinion,” the Task Force wrote in one of the more pointed passages of The Federal Connection. “The need for secrecy, given wartime conditions and the urgency of the Manhattan Project, was perhaps understandable. What is inexcusable, however, is that the cloak of secrecy seems to have been used to conceal pertinent, ostensibly non-secret information from those who had a ‘right to know.’”

For the next two years, 1945 and 1946, the Linde wells kept clogging up. Each time it happened, which was often, the wells had to be shut down and cleaned, while the effluent was discharged into Two Mile Creek. No matter what Linde and the Army tried, the wells continued to clog. More wells were dug, and they immediately started clogging too. Linde was forced to dump its radioactive effluent into a drainage ditch along the side of its property, where it would eventually run off into Two Mile Creek. The wells kept backing up.

Linde did not like being forced to dump their wastes like this. The ditch was unprotected as it ran into the creek and through the public park and golf course. Linde officials asked the MED repeatedly for permission to dig more wells. The Army repeatedly denied permission, stating that it cost too much money. The pressure under which Linde officials were operating, as well as their fear of ruin, is evident in this 1945 Linde memo: “We are unwilling to divert this hot lye water effluent to Two Mile Creek because of the liabilities involved, although the Army has requested that we do so in spite of their unwillingness to write us a letter ordering us to put the effluent in the creek and absolving us from any legal action, criminal or civil, which might result.” The memo also provides insight into how the Army avoided responsibility; it serves as an example of the cold and bloodless relationship the Army maintained with its partners.

“Incredibly, despite Linde’s warnings of danger and scientific analysis,” the Task Force wrote, “MED recklessly continued to dispose of its hazardous liquid wastes into Two Mile Creek.” And in all the time since those events occurred, the Task Force noted, from 1946 until the publication of The Federal Connection, nothing had been done to those wells or the ditch. Nothing. There were no records, nor had there been any attempts to call attention to the wells or the need to inspect them or determine a clean up plan. They were never mentioned, by anyone.

“What we were talking about with the Linde wells, way back then, was just like fracking,” Smitty reflected. “We were questioning the wisdom of injecting waste into wells in the first place. The dolomite rock below the surface in the Niagara Region can be dissolved very easily. Who knows where that caustic effluent goes when it gets down into the ground water? It’s the kind of thing that Hinchey and I saw at many of the war plants. In each case they flushed their chemical wastes into the sewers or into the ground. Maurice became a strong opponent of fracking. We all did. It’s an attitude we developed at Love Canal.”

With the Linde story, the Task Force had documented the Army’s willingness to take risks and plunge into the untried and the unknown, with little thought for the consequences. By forcing the contaminated liquor into the wells, the Army and its industrial partner were conducting irreversible chemical experiments on the environment, taking risks which they did not completely understand, but which they knew were dangerous. The Task Force demonstrated next that the Army also did experiments on the soldiers and civilians who worked on the Manhattan Project, exposing them for long periods of time to excessive levels of radiation when there was very little that was known about the effects.

Scientists understood in the early 1940s that high doses of radiation were deadly, but they did not yet fully understand the cumulative effects of continuous exposure to lower levels. By the time the Task Force began their investigations in the late 1970s, the dangers of low level radiation exposure were much better understood. Nevertheless, the Army had not looked back, and the Task Force harshly criticized the Government for it. “Even though studies have resulted in better worker protection, little is known about the health histories of workers who were exposed during World War II and after in Western New York. The men and women who worked at Linde Air Products and Electrometallurgical Co., and later at Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, Simonds Saw and Steel, Bethlehem Steel and other locations may have been the unwitting casualties of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Bikini atoll, and the Cold War arms race.”

According to one war time Hooker employee, Fred Olotka, who worked in the plant that processed the uranium slag sent over from Linde, the workers were never told that they were handling uranium. “In those days, we had no idea whether this material was radioactive. We did not know it was uranium… it had to be after the war effort had ended that they indicated to us what the materials were that we have handled and where they went.” The truck drivers who hauled the radioactive sludge from the ceramics plant to either the Haist property or the LOOW were never told what they were carrying, nor that it might pose any kind of danger to them or the neighborhoods through which they passed.

“Whatever their sacrifices may have been, it has gone unacknowledged by Federal authorities," the members of the Task Force wrote. "There is no evidence that officials have ever looked into the health histories of these workers. Clearly the secrecy and internal security of the Manhattan Project meant that workers who were exposed to radiation were unaware of what was happening to them. Without the knowledge of the materials they were working with, the workers were unable to advocate on their own behalf for safer, cleaner working conditions. The amount of danger which workers confronted in the workplace was decided by scientists and engineers based on experiments with laboratory animals, for the most part…. At times, the needs of the war effort forced worker safety into a lower priority than might have been the case in peacetime.”

In other words, the workers were as expendable to the Army as the wells, the aquifer, the Niagara River, and the Falls themselves. Exposure rates were not kept ALARA, or “As Low As Reasonably Achievable,” but as high as they could reasonably justify. Put simply, more work gets done if you are less encumbered with regulations. The Task Force came to the conclusion that the “science” that was used to justify the exposure rates was based on “hearsay,” not evidence. It was a matter of finding whatever science could be used to justify the original plan.

“There was a clear realization that safety could be had only at the expense of production, and the needs of the war effort superseded the obligations of the project to protect its workers.” The Task Force insisted that the very least that the Army could do for the men and women who had loyally served their country was to conduct a thorough health study.

“I don’t think that ever happened,” Smitty noted grimly. “I don’t think they ever really acknowledged what they did to the civilians who worked in the plants. And to their families. When I talked to people around Niagara Falls, they had a much better understanding than they did 35 years earlier, during the war, about the dangers of radiation exposure. And they knew that they had been exposed. People had serious questions about their health, and wanted to know if they were in danger, or if the government was going to do anything about it. But as you know, government health officials will tell you that there are many things that can cause cancer. So unless a study were done to link the cancers directly to the exposures, all the people could do was speculate, and worry. They weren’t going to get any help.”

The Task Force had only one more story left to tell in The Federal Connection, and that was about the LOOW, or Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, a large tract of land in the towns of Lewiston and Porter, eight miles north of Love Canal. “This we saved for last,” Smitty told me, “because it kind of sums everything up. Here you see the big picture. You see the Government’s total disregard for the environment and all the people, not just the ones who worked in the plants, but everyone who lived nearby. They made a complete mess of the place, then couldn’t even get their stories straight.”

The Task Force put it this way: “Part of the LOOW story that has never been told, prior to this report, is the way in which the conditions at the LOOW were created and fostered by federal policies. Documentary evidence compiled by the Task Force discloses the extent of federal mismanagement at the site, as it is manifested by sloppy record-keeping procedures, inadequate mapping of buried wastes, and technological primitivism with regard to waste storage and disposal.”

World War II poster

World War II poster Even though the LOOW was only used for a short time, the Army’s activities managed to badly contaminate the area with TNT wastes and residues. That, unfortunately, was only the beginning. In 1944, the Chemical Warfare Service took over 1100 acres of the site for the “temporary” storage of munitions and chemicals. Also in 1944, the MED took over part of the LOOW for storing radioactive sludge from the LInde plant and other sites. After the war, the Atomic Energy Commission was established and superseded the Manhattan Project. They used their portion of the LOOW as a waste disposal site for contaminated materials from all over the Eastern US.

The danger posed by siting a chemical dump on top of contaminated infrastructure was recognized immediately by the War Assets Administration which had been charged with managing and disposing of the LOOW right after the war. They had been hampered in their work, however, by the Army’s lack of cooperation in providing them with information.

The WAA hired a consultant in 1948 to research the site and figure out what needed to be done to the property before it could be sold. Their consultant told them that the site was so polluted that, “100% decontamination is almost impossible,” and that the property “should be condemned for future use and fenced and posted accordingly.” But according to the Task Force, these words of warning were ignored by the Government, and “then forgotten by the succeeding generations of bureaucrats.”

Within a few weeks of the issuance of the consultant’s report in March 1948, the Atomic Energy Commission was given expanded control of the entire LOOW. The pressing problem confronting the War Assets Administration had therefore been solved. But the problems posed by the TNT contamination were simply swept aside and forgotten. When the Task Force asked the AEC for documentation about TNT contamination, they were given nothing. The AEC claimed they had no records.

All of the problems associated with TNT wastes were compounded with the introduction of chemical and radioactive wastes to the site. The Task Force criticized the Government for adopting a policy of “expediency and economy” in its federal storage and disposal program. They specifically condemned “the dumping of radioactive wastes in open, and often unmapped pits, in rusting barrels stacked along the road side, and in inadequate structures originally designed for much different purposes. Inevitably, these practices resulted in the contamination of the LOOW site and in the leaching of radioactive contaminants off the site, onto land outside of the control of the Federal Government.”

A radioactive who’s who of wastes made their way to the site through the 1940s and 1950s. The higher quality African ore that was processed at the Linde Ceramics plant generated a by product of sludge that contained significant levels of radium. Unlike the lower grade sludge that was hauled to the Haist property as waste, about 18,000 tons of the quality African sludge was stored at the LOOW for eventual retrieval by a Belgian owned metals company based in Katanga that had retained possession of the material in its contract with the Manhattan Project. The company intended to retrieve the sludge after the war, but never did. "I called them and asked them if they were ever going to pick it up." Smitty explained. "They told me to forget it."

In addition to this locally supplied radioactive waste, other wastes were brought in from around the country. The Task Force noted that the Cold War had led to the build up of atomic waste as well as atomic arsenals. Contaminated and radioactive materials came into the LOOW from Missouri, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, and Massachusetts. Storage was haphazard and dangerous. Radioactive material leaked into the ground.

Of all the materials being brought in, K-65 uranium ore residues had the most radium concentration and were therefore considered the most dangerous. In fact, by 1995 the Nuclear Regulatory Commission had determined that these residues were as hazardous as High Level Radioactive Waste. They originated at a processor in St. Louis, the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, and at Linde. The K-65 residues were stored at the LOOW in old TNT igloos, but it soon became evident that the amount of radiation in the igloos drove the interior radon levels far too high. After storing 96 drums for one day in one of the igloos, radiation levels rose to 71 times higher than the human tolerance level. The drums were taken out of the igloos, but they were left along the railroad line and the roadsides for a number of years.

A concrete silo that was used for the storage of K-65 residues cracked soon after being put in service, prompting the AEC to stack more drums along roads where the metal soon deteriorated and the radioactive contents leaked into air and land. The Niagara Frontier is infamous for its wet windy winters and lake effect snow. Eventually, drums of K-65 were shipped back to Fernald, Ohio.

“I could not get out onto the site, but I could see all over the LOOW from the roads,” Smitty explained to me. “It was all so wide open, I could see everything that was there. I could see the rusting drums lined up along the edge of the road. The same ones with the radioactive ore in them. So many of them were still there.’

The last problem with the LOOW taken up by The Federal Connection concerned the ammonium thiocyanate that the AEC allowed the Carborundum Metals Company to dump at the LOOW in the mid 1950s. Carborundum had been refining hafnium and zirconium for the AEC’s reactor program. 350,000 gallons of ammonium thiocyanate filled a lagoon on Carborundum property and could not be disposed of without killing off the fish in Tonawanda Creek. The AEC and the NYS Department of Health gave permission for the material to be dumped at the LOOW on a one time only basis, but the dumping continued for about a year at the rate of 12,000 gallons a day, for a total of roughly 4 million gallons. It is impossible to establish an accurate number because records were not maintained.

The records that do exist, however, indicate that AEC and Carborundum officials, as well as Hooker officials who were custodians for the LOOW at that point, were all more concerned with legal liability than they were with damage to the environment. They allowed a company to dump millions of gallons of contaminated material into a system that flowed directly into the Niagara River, an international waterway. Canada was never informed.

Ultimately, parts of the LOOW have been recycled for different purposes. The Army used part of it as a Nike missile base, and the Air Force used part as a test site. A real estate firm bought a big piece in 1966 for less than $100,000. Part of it went to a disposal company, Services Corporation of America, which uses it as a waste treatment and disposal plant. Radioactive waste from the Manhattan Project is still stored at the LOOW.

“Any kind of strange experiments they wanted to try, they would do out there and then abandon them, and then try new experiments,” Smitty told me. “But all of that was over and done with by the time we got there. From a distance, it looked like an industrial city like Pittsburgh gone to rot. No smoke, nothing moving, everything falling apart. It was all very mechanical, and all a big production.”

The members of the Task Force felt that the LOOW illustrated what they called a “startling and disturbing breakdown of institutional memory.” Tests and surveys had been conducted in the late 1940s and again in the 1950s that identified some of the toxins that were buried and where they were located. But years later, when the land was sold, all of this information had been lost and forgotten. Vital information disappeared when one group of bureaucrats took over from another. Most unforgivable of all, however, was that throughout the brief history of the LOOW, “Federal officials misled local government representatives and the public concerning the nature of federal activity at the site, and the extent of the radiological hazard at LOOW.” The Government, according to the Task Force, was not to be trusted.

As the Task Force was wrapping up its investigation, Assembly Speaker Stanley Fink lobbied President Jimmy Carter to get the Federal Government to assume a larger role in the Love Canal clean up. He spoke with the President in November of 1979. By early 1980, Carter appointed Fink to the State Planning Council on Radioactive Waste Management. According to Smitty, Assemblyman Hinchey was optimistic that the President was going to respond to The Federal Connection and allocate more resources to the Niagara Frontier and continue the investigation into who was responsible.

Smitty was not so confident. “I was pretty sure that nothing was going to happen when we released our report, and I’m afraid that I was right. The counsel for Stanley Fink, and maybe even Fink himself, went down to see Carter around 1979. They told Jimmy that it was going to get very uncomfortable for him because New York was going to open this Love Canal story up, and reveal the extent of the Federal Government’s role. They told Jimmy that I had found more in my trips to the archives, and that it was compelling. These discussions were not publicized. I can only go by what Stanley Fink told me.”

According to Smitty, Fink had threatened to subpoena the federal officials and force them to attend a hearing in Albany to talk about the contamination of Niagara. “It was unheard of for a state to subpoena the Federal Government over wrongdoing, so the feds came to Albany cooperatively, no subpoena necessary.”

“The pentagon officials, while in Albany, acknowledged that our report was correct,” Smitty continued. “They were civilians from the Department of Defense. They wanted no record of this meeting. It was very informal. And polite. There were no arguments about anything. They just basically nodded their heads and agreed with the things we were saying. Fink and the rest of us sat on one side of the table, and the pentagon civilians sat on the other side. It was a green topped table. We would ask them questions, and they would look at each other as if to say, ‘who wants to tell the next lie?’ They agreed to allow us to look at more records, so shortly after the meeting, I went down to the Pentagon one more time.”

Smitty recalled that there was some press coverage, but that “no one drew the right conclusions from the meeting.”

NBC Nightly News with John Chancellor ran a story on May 31, 1980 about The Federal Connection: “A task force of the New York legislature charged that Hooker Chemical may not have been the only one dumping at Love Canal. It said there’s evidence the U.S. military dumped dangerous wastes there in the 1940s and that some of the wastes could have come from nuclear projects. It said that dumping may have occurred elsewhere, too, north of the canal at nearby Lewiston, and south along the Niagara River…But federal officials do not believe the government dumped dangerous wastes in the area … The Defense Department said Friday that it had found no evidence in its records to support charges that the Army had ever dumped toxic wastes in the Love Canal area…”

A similar story appeared the same day in The New York Times: "George Marienthal, a deputy assistant secretary of defense for energy, environment and safety, said in a statement Friday: 'The Department of Defense takes exception to the New York State Assembly Task Force report as we found no evidence to suggest that previous, comprehensive Army and interagency task force reports, which found no Defense Department dumping program to have existed in the Love Canal area, were deficient.'”

The Assistant Secretary went on to deny any possibility of Army dumping at the other sites mentioned by the Task Force in its report. He hinted that the Army might conduct another investigation, but it never did. The news media paid no more attention to the matter.

The Federal Connection was filed several months later, and there it died. One can find reference to it in the New York State Library and the Assembly archives as The Assembly Task Force on Toxic Substances Sub-agency history record. This document records the three major recommendations of the Task Force: “1) The New York State congressional delegation should sponsor legislation providing additional federal funds for Love Canal remedial programs and for health studies of individuals whose health was affected by contamination; 2) the Department of Defense should reopen its investigation of military involvement in chemical production and disposal of wastes; and 3) the records gathered by the Task Force should be turned over to the New York State Attorney General for possible legal action against the federal government.”

None of these three things ever happened. Jimmy Carter lost his bid for re-election in the fall of 1980, and President Reagan’s administration was far less cooperative with the New York State Assembly than his predecessor had been. In fact, many of the documents that Smitty had used in his research were reclassified under Reagan. Still, the Assembly archives tried to put a positive spin on the work of the Task Force:

“The main success of the Task Force investigation was to call attention to federal government involvement in toxic dumping in the Niagara Falls region. The Task Force called on the federal government for the first time to acknowledge responsibility for dumping and to accept responsibility for further testing and cleanup. During the 1980's, the

Environmental Protection Agency continued to do extensive testing and monitoring of contamination in the region. The federal government however, has not assumed responsibility for contributing to toxic contamination of the region.”

The whole experience left a bad taste, according to Smitty. He told me that he and Maurice were “offended by our government.” The more they learned about the contamination of Niagara, the more Government officials began to appear to them like organized crime figures in their willingness to lie, deliberately deceive, and contribute to human suffering. Smitty noted little difference between the operations of the Government and those of the mob. Ultimately, they worked hand in glove with each other.

The Task Force had recommended that the Defense Department reopen its investigation into the contamination at Love Canal and continue that investigation until the Army personnel who were seen dumping by eyewitnesses could be identified. I asked Smitty if he would still like to see that come to pass. “Why bother,” he answered me. “What is the good, at this point, in blaming individuals, whether it is General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, or Roosevelt, or Truman, or anyone else? They are all dead.”

The Federal Connection also pokes holes in Truman’s claims about the effectiveness and “unique success” of the combination of “science and industry” working under the direction of the United States Army. The Task Force has shown us how that combination really functioned: how industrialists and Army officials scrambled to push responsibility and liability onto each other as they knowingly violated laws of decency and common sense by dumping poisons into sewer systems, streams, and the international waters of the Niagara River. We have seen how the Army abandoned its partners in science and industry when the bills came due for environmental clean up. And we have seen how the Army and the industrialists have hidden the history of their work and the contamination that they have produced, leaving future generations without the knowledge they need to protect themselves.

The Federal Connection may also help us to understand better the claims that Truman made about winning “the battle of the laboratories,” and “the greatest scientific gamble in history.” The Task Force has shown us what that battle and gamble looked like as it played out in Niagara Falls, and how much it may ultimately cost. It enables us to better understand what was certainly happening in Germany and Japan as both countries raced to produce more powerful weapons too, leaving behind a legacy of radioactivity, contamination, broken landscapes, and lives.

The Federal Connection shows us that if, indeed, the battle and gamble were won, it was because of the frantic pace and the reckless drive to build the bomb no matter what the cost. We begin to see that the mandate to build the bomb took precedence over everything, often banishing reason and human feeling in accordance with its cold demands. In fact, we see how the race for the bomb took on a life of its own, and once begun, could not be stopped.

The human race had walked into a trap of its own making. Our military leaders went into World War II thinking it would be like World War I. They ordered up vast stocks of phosgene gas and impregnite. But the race to manufacture the ultimate weapon overtook those old weapons, and led us all into something much different. The decision to make the bomb was made under duress: Einstein had written to Roosevelt that the Germans were working on a bomb. Once the decision to beat them to it was made, there was no turning back.

The Federal Connection may lead us to question whether or not we actually won that enormous gamble. Yes, the bomb hastened the end of the war, but the question has to be asked whether even that major victory was worth the price. The final cost of the Manhattan Project has yet to be reckoned, but the toll keeps climbing higher. We have seen that the Niagara Frontier is still home to a large number of radioactive hotspots, tracts of land that will never support life as we know it, but that have to be monitored forever.

The many Manhattan Project sites around the country all tell the same story. There is intractable radioactivity at the Hanford reactor in Washington; in New Mexico; and in Rocky Flats. The Army’s reckless attitude toward disposal methods during and immediately after the war will take generations to undo. Perhaps the damage is irrevocable. In recent weeks we are learning that even our fail safe, underground, nuclear depositories buried deep in salt vaults in New Mexico are leaking radioactivity.

Since humankind first started manufacturing fissionable materials, we have proven ourselves unequal to the task of handling them. The carelessness of the Army and its partners, as outlined in The Federal Connection, contributed to widespread contamination, leaks, exposures, and even the loss or theft of atomic fuel. Trillions of dollars would be required to remove the atomic waste from all of the sites, but even then, we still don’t know how to dispose of the material. We do not know how to protect ourselves and future generations from the radioactivity.

But while we may not know how to handle radioactivity, radioactivity knows how to handle us. It has become our master instead of our servant. Its presence in the world sets new parameters for the way we think and live.

Harry Truman illustrated this when he spoke about secrecy. He may not have had first hand experience with many aspects of the Manhattan Project, but secrecy he understood. Until April 1945, when Franklin Roosevelt died and Vice-President Truman was sworn in as President, he had no knowledge of the Manhattan Project or that it even existed. In four months, he went from being completely in the dark to being the one to give the order to drop the bomb.

Reading from a speech that had been carefully prepared for him many weeks in advance, he said, “It has never been the habit of the scientists of this country or the policy of this Government to withhold from the world scientific knowledge. Normally, therefore, everything about the work with atomic energy would be made public.”

It was almost an apology. Up until this time, America did not have to keep very many secrets. But now it did. The Manhattan Project was so secret that the men and women who put it together had no real sense of what they had been doing. Tens of thousands of people did their part guided solely by obedience and trust, starting with the men and women in Niagara Falls who unloaded the uranium ore that had been shipped from Africa by way of Canada, and finishing with those who sailed to Tinian Island aboard the USS Indianapolis and transferred the bombs onto the planes that dropped them over Japan. Nothing had ever been organized like this in the world before.

Truman blamed the need for secrecy on the demands of the moment, that is, the war, the race to be first, and the nature of the nuclear weaponry itself. According to Truman, these were not normal times, and these were not normal weapons. The war and the technology forced the Government to keep secrets. People had no choice but to behave the way they did. It was why the Army Captain had to scare the boys of the Love Canal Gang away from their swimming hole as he hid away canisters of explosive garbage. It was why the Army couldn’t tell the Niagara Falls City Council that the Army and Linde were flushing radioactive particles down the municipal sewers. It was why the men and women who worked all day in the plants returned home in the evening and embraced their spouses and children without caution, oblivious to the fact that tiny particles of radioactivity were clinging to their clothing.

We want to blame human agents for situations like this. People are the ones with political and moral motivations, not things. But in truth, the situation and the technologies often make demands of their own, forcing choices and forcing events. This idea is not new. Taking up the question, “Do artifacts have politics,” Langdon Winner wrote in 1986: “The atom bomb is an inherently political artifact. As long as it exists at all, its lethal properties demand that it be controlled by a centralized, rigidly hierarchical chain of command closed to all influences that might make its workings unpredictable. The internal social system of the bomb must be authoritarian; there is no other way.”

He went on to say that it does not matter what kind of political system is in place. Once the bomb is introduced, it will demand authoritarian conditions. “Indeed, democratic states must try to find ways to ensure that the social structures and mentality that characterize the management of nuclear weapons do not ‘spin off’ or ‘spill over’ into the polity as a whole.”

But, of course, they have spun off. That's why Truman’s speech ends up sounding to us more like a threat, or a grim promise, than an apology. He told America and the world that the culture of secrecy will have to remain in place for awhile, given the great work that had yet to be done. “... under present circumstances it is not intended to divulge the technical processes of production or all the military applications pending further examination of possible methods of protecting us and the rest of the world from the dangers of sudden destruction.” In other words, this enriched uranium puts everyone on the planet at risk, so trust us. We will keep it from getting into the wrong hands... for as long as it poses a threat... which is pretty much forever...

One can draw a direct line from the culture of power and secrecy that grew up around the Manhattan Project, to our present looming fears about lost civil liberties, total surveillance, terrorism, counter-terrorism, and a global police state. Atomic bomb technology establishes a one sided power relationship between those who wield the power of life and death, and those with no comparable power at all. It establishes a social order built on raw strength, inequality, stealth, and distrust. It makes our world as unstable as the uranium 235 isotope.

Our reading of The Federal Connection may have given us some insights into Truman's threat; it may also help us better understand what President Eisenhower was talking about, 15 years later, when he warned about the "military industrial complex" and "the permanent armaments industry." The Federal Connection has given us a glimpse of the military industrial complex in its infancy, how it got its way, and how it abused an entire region of New York State without taking any responsibility for it. We can understand better now just what Eisenhower's words imply, and what kind of threat to our way of life he feared.

Unfortunately, we can also see that the Task Force's best efforts on behalf of environmental justice had little or no effect on the US Government. And Dwight Eisenhower, while pointing out there was a major problem, didn't offer us any solutions, or advise us how we might make Government and industry behave less destructively. All of that we are still going to have to figure out for ourselves.

“The truth is all there,” Smitty said to me at the end of a very long evening. “But people have to be willing to look at it directly and say something about it. The Government is not going to deal straight with you, and they certainly are not going to help you, but you can’t just lie down and let them tell you how things are going to be. You have to keep bashing on.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed